Letby trials #1 - Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial must be defended

Some background on becoming involved in the trials of Lucy Letby

"Truth is the daughter of time, not of authority."

Francis Bacon

“Yesterday the New Yorker magazine published a 13,000 word inquiry into the Lucy Letby trial, which raised enormous concerns about both the logic and competence of the statistical evidence that was a central part of that trial. That article was blocked from publication on the UK internet, I understand because of a court order. Now I’m sure that court order was well intended, but it seems to be in defiance of open justice. Will the Lord Chancellor look into this matter and report back to the house?”

Sir David Davis, House of Commons, UK Parliament, May 2024, using Parliamentary privilege to break through a court order that was creating a distorted UK information environment on the Letby trials.

Two weeks ago, on 10th September, The Daily Telegraph ran a page 2 piece, highlighted on the front page, summarising my views on the Lucy Letby trial and the safety of the convictions, convictions that underpin the most serious sentences given in the United Kingdom since the abolition of the death penalty.

The Telegraph article also acts as a ‘TLDR’ for this piece, a short summary for a wide audience. So if you don’t have a deeper interest in the case, I suggest going with that, posted in the photos below. A slightly longer form of it is available online here.

Larger size in 3 separate images:

[Note, I do not have a formed opinion on whether or not revisions to Jury processes is the right way to address the problems that I think are revealed by this case, I have an open mind on solutions, and worry that alterations to jury rules could give too much power to the judiciary].

That article was based on a draft of a piece I had written and shared with them to use.

What follows is a slightly revised version of that draft piece, with []’s clarifying some statements that the passage of time has rendered out of date, such as “2 weeks ago” now becoming 1 month ago.

I have put this out now for reasons that will shortly become clearer.

There are the following sections:

Background: the most severe convictions and sentences in the UK since the abolition of the death penalty.

Escaping an information bubble: Reading Rachel Aviv’s New Yorker article in May 2024 whilst in the US & seeing an alternative reality.

Breaking through the court order: Sir David Davis’ parliamentary intervention unlocked access to a wide range of information and voices that were not yet public.

Pattern matching: features of the Aviv article narrative resonated with my experience on COVID response.

Deep dive: an intensive look at the available evidence in August led me to conclude with effective certainty that the Letby convictions are unsafe.

Open justice: Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial must be defended publicly, with open scrutiny and debate.

With thanks to the friend with a legal background who spent this evening reading through this and providing edits to improve clarity. They wish to remain anonymous.

[Update Friday 4th Oct - the BBC and TriedByStats are now publicly reporting that Letby had never been on shift with Baby C at the time the crucial evidence that flipped that case to a murder charge was obtained - see second blog here.].

Background - the most severe convictions and sentences in the UK since the abolition of the death penalty

I explain here why I have become vocal on the issue of the safety, or lack of, of the Lucy Letby convictions, and how I came to be involved. This is a lot longer than it could be precisely as it's a kind of testimony of events leading up to my involvement in the Letby trial debate and, given how sensitive and difficult this issue is, I am erring on the side of writing too much rather than too little to ensure proper context. Writers can then select from it as they find useful to quote if they wish. I know this is ‘too long’ - the Telegraph piece serves as a short summary.

I am receiving many questions on this and I’ve tried to be comprehensive in addressing them. If you are looking for a dissection of each point for and against Letby’s innocence or guilt, this isn’t the piece for you. Partly because there is a lot I can’t yet say publicly on that, I’m saving that for later (soon). I suggest reading the New Yorker article and other reporting discussed below as a starting point: the New Yorker article has withstood the best scrutiny I have been able to give, and some of the biggest issues are not in the piece.

You will, if you live in the UK, have heard of Lucy Letby. Her case attracted international attention. If you have forgotten the name, she is the nurse described by the BBC as ‘probably the most notorious serial killer of modern times’ and the ‘most prolific baby killer in modern times’. She was working on a neonatal unit (a unit that specialises in the care of premature babies), and was found guilty of 7 baby murders and 7 attempted baby murders, and was given the severest sentence in the British state since the abolition of the death penalty - receiving multiple whole life orders (each of which means that, unless overturned, she essentially has no possibility of ever leaving prison). The most recent of these sentences was only given ten weeks ago, following a retrial of a case the first Jury could not reach a conclusion on.

The media seemed convinced she was guilty until recently. As Rachel Aviv, author of the New Yorker article, said in an interview in May 2024, “So far the media coverage in the U.K. has treated Letby’s guilt as a foregone conclusion.” Yet, as she says in the same interview, “Cleuci de Oliveira, an incredible researcher I work with, pointed me to the Letby case last spring, when the trial was still underway. We were both struck by the fact that the case seemed to hinge almost entirely upon the belief that there had been too many deaths to have occurred by coincidence.”

During the trial itself, I remember wondering if the cluster of deaths in this ward could be a statistical coincidence. It may be a near instinctive reaction of someone scientifically trained, as scientific research often centres on separating real signal from chance. But whilst something about it didn’t sit right with me, I assumed this statistics question and related points would have been robustly scrutinised at the trial, as I have a lot of confidence in the British judicial system in broad terms. I didn’t see any clear reason to justify digging deeper at the time.

Why, then, have I seemingly suddenly switched over the past 2 weeks [now month] to tweeting in a focussed way on the topic and repeating phrases like ‘Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial must be defended’, and describing myself as a ‘campaigner’ [30th august] for Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial? Several people messaged me saying some variant of, to quote one person directly ”wow, you have gone all in on letby trial”.

It isn’t as sudden as it may appear and I did not take the decision lightly.

This piece explores this, and has three broad purposes:

It is partly a summary of things I have said in tweet form over the past 2 weeks [now a month ago], but not yet combined in a single, readable place.

It is partly an exercise of putting things into public domain for others to quote from as needed, so I have not focussed on brevity.

It is also a response to some criticisms of those of us scrutinising these trials.

I note that I’m relatively late to the game on this - groups like Science on Trial, Tried by Stats, Peter Elston’s podcast and others have been way ahead. Writers like Philip Hammond at Private Eye have been on the case long before me, as have many groups of concerned citizens. Ruxandra Teslo was trying to raise concerns last year. I’m just explaining my own thought processes, not claiming to have been there first.

Things have moved so quickly much of this doesn’t seem so surprising anymore. 2 weeks ago [now 1 month] I was at the ‘very optimistic’ end of views of how quickly the safety of the Letby conviction could be ascertained, but even I’ve been very surprised at how quickly the narrative is changing.

Nothing in here should be misconstrued as anything other than my own view unless stated otherwise.

Escaping an information bubble: reading Rachel Aviv’s New Yorker article in May 2024 whilst in the US & seeing an alternative reality

From Saturday 27th April to Saturday 11th May of this year I was in a monastery in the middle of a forest in very rural America, I think a 30 minute drive from the nearest large convenience store. I had no contact with the outside world at all, not even a brief check of twitter, nor any news came in. I was essentially in complete silence. It's a long story for another day how I ended up there.

Afterwards, I began reconnecting. On Monday 13th I found a New Yorker article by Rachel Aviv which I began reading. The article was titled “A British Nurse was found guilty of murdering 7 babies - did she do it?” That UK twitter was complaining that it was blocked in the UK may have piqued my interest. Note that it remains blocked in the UK, though this is not due to a court order (I know the reason but cannot disclose it).

As I happened to be in the US, I was able to read it. What I read I found quite shocking. There were potentially, and I emphasise potentially at that stage, many nontrivial and very serious problems with the trial and convictions of Lucy Letby. If the facts in the New Yorker piece held up to scrutiny, then it would potentially be the worst miscarriage of justice in recent British history.

It piqued my interest for a number of reasons:

Heavy and critical reliance on science and medical evidence: The case appeared to depend largely upon scientific/medical (herein, ‘scientific evidence’) evidence, and how different pieces of scientific evidence relate to one another and alter each other’s interpretation. I had seen first hand how institutions can struggle to deal with this. Whilst there was non-scientific evidence at the trial, relatively little appeared to hinge on it compared to the scientific evidence. If the scientific and ‘expert’ medical evidence was removed, it appeared the case would collapse.

Expected institutional failings: Relatedly, some of the claims in the Aviv piece pattern matched closely my own intuition for how human organisations would behave under those circumstances - it seemed highly plausible.

My family background: My mother is a retired nurse, as is my godmother, and I spent substantial amounts of my childhood around nurses. The newsletters of the nursing profession were a regular arrival through our family letter box. I also spent time as a ‘mock patient’ in nursing exams at the University my mother taught at (she switched to become a lecturer in nursing after my younger brother was born). My father is a (nearly retired) doctor. So, my childhood was full of hospital stories, the doctor-nurse dynamic, etc etc.

A window of opportunity due to chance: Reporting on it was banned in the UK, meaning there might be an opportunity to make an impact through having read this article whilst in the US, as few in the UK would have the relevant information. This and the connections I had from my time in Number Ten relating to the intersection of science, technology, & other fields meant I might have an ability to nudge things in a positive direction if needed.

Now, I am not an expert in the areas of science and medicine most relevant to this case. Notably, no one person is a deep expert in all of them (a similar situation to COVID). But I had been in 10 Downing Street and what is now the science department (DSIT) during the COVID crisis, joining in April 2020. There I saw the worlds of science, medicine, law, and governance collide, and it was a core part of my job to navigate those challenges, and integrate the different strands. I’d seen how well meaning groups of people can get this dramatically wrong, how hard it can be to detect when such mistakes are occurring, and how compelling false information can be to non-experts, when it comes from experts.

In that #10 role there were a number of occasions where I felt there were significant errors being made at the intersection of science and other fields, and where I tried, with varying degrees of success, to fix that/raise the alarm.

Two examples illustrate this: the origins of the UK rapid testing program and the origins of COVID. To varying degrees, a confident yet unsafe consensus on these issues because key decision makers did not have accurate scientific information or the skillset needed to understand the situation sufficiently and holistically, and there was, especially on COVID origins, a lack of open debate on the issue reinforced by the clear reputational and career consequences for disagreeing with the ‘consensus’. Further, strong institutional incentives worked against both of them. Today, that using lateral flow tests to help mitigate the impact of COVID on schools, hospitals, and more was a good idea is not controversial, nor is the possibility that COVID came from a lab accident. Both were once viewed as fringe theories.

My involvement in these two issues is covered in Statecraft (for rapid testing) and my blog here quoting The Times (for COVID origins and events in April 2020 when I raised this issue, at the time as a lonely voice). In both cases, I decided to elevate the issue to the highest appropriate level that I could.

My pattern recognition circuits began strongly tripping the same features as I delved deeper into the Letby case. It's worth noting that in all of these cases, amateur/fringe/outsider groups, rather than the mainstream voices, got there first. The armchair detectives were the first detectors.

4 months ago the view that the Letby conviction was deeply unsafe sat very much in the fringes, even being consigned to the seemingly ever growing category of ‘conspiracy theory’. A KC, Peter Skelton, gave a quote to the BBC in July referring to conspiracy theories about the case. But there is no need to hypothesise a conspiracy for the conviction to be deeply unsafe.

As I read the New Yorker piece, I became increasingly deeply concerned. However, the court order meant that the piece appeared, in terms of media narratives, to have come out of nowhere, a bright sudden flash of attention that provided a glimpse into an alternative reality.

The court order was, in my understanding, there for the protection of both Letby and prosecution so that only information deemed admissible to court could influence the Jury. It rightly aims to prevent journalists from finding people guilty ahead of time and “preventing a fair trial”, yet it appeared to be seriously misfiring here and was risking “criminalis[ing] people raising the alarm about potential miscarriages of justice”, as Guardian investigations correspondent David Pegg later phrased it to me on Twitter toward the end of august.

This court order therefore posed substantial challenges for drawing attention to, and working on, this potential alternative reality in which Letby may in fact have been the victim of the worst miscarriage of justice in recent British history, and was potentially in urgent need of help.

The Aviv article contained text from Letby’s own notebook, containing the famous “confession”, in its fuller context. Here is some of that article:

“[A] Cheshire police detective knocked on Letby’s door. Two years earlier, she had bought a home a mile from the hospital. A small birdhouse hung beside the entrance. It was 6 a.m., but she opened the door with a friendly expression. “Can I step in for two seconds?” the officer asked her, after showing his badge.

“Uh, yes,” she said, looking terrified.

Inside, she was told that she was under arrest for multiple counts of murder and attempted murder. She emerged from the house handcuffed, her face appearing almost gray.

The police spent the day searching her house. Inside, they found a note with the heading “NOT GOOD ENOUGH.” There were several phrases scrawled across the page at random angles and without punctuation: “There are no words”; “I can’t breathe”; “Slander Discrimination”; “I’ll never have children or marry I’ll never know what it’s like to have a family”; “WHY ME?”; “I haven’t done anything wrong”; “I killed them on purpose because I’m not good enough to care for them”; “I AM EVIL I DID THIS.”

On another scrap of paper, she had written, three times, “Everything is manageable,” a phrase that a colleague had said to her. At the bottom of the page, she had written, “I just want life to be as it was. I want to be happy in the job that I loved with a team who I felt a part of. Really, I don’t belong anywhere. I’m a problem to those who do know me.” On another piece of paper, found in her handbag, she had written, “I can’t do this any more. I want someone to help me but they can’t.” She also wrote, “We tried our best and it wasn’t enough.”

After spending all day in jail, Letby was asked why she had written the “not good enough” note. A police video shows her in the interrogation room with her hands in her lap, her shoulders hunched forward. She spoke quietly and deferentially, like a student facing an unexpectedly harsh exam. “It was just a way of me getting my feelings out onto paper,” she said. “It just helps me process.”

“In your own mind, had you done anything wrong at all?” an officer asked.

“No, not intentionally, but I was worried that they would find that my practice hadn’t been good,”she said, adding, “I thought maybe I had missed something, maybe I hadn’t acted quickly Enough.”

“Give us an example.”

She proposed that perhaps she “hadn’t played my role in the team. I’d been on a lot of night shifts when doctors aren’t around. We have to call them. There are less people, and it just worried me that I hadn’t called them—quick enough.” She also worried that she might have given the wrong dose of a medication or used equipment improperly.

“And you felt evil?”

“Other people would perceive me as being evil, yes, if I had missed something.” She went on, “It’s how this situation made me feel.”

The detective said, “You put down there, Lucy, that you ‘killed them on purpose.’ ”

“I didn’t kill them on purpose.”

The detective asked, “So where’s this pressure that’s led to having these feelings come from?”

“I think it was just the panic of being redeployed and everything that happened,” she said. She had written the notes after she was removed from clinical duties, but later her clinical skills were reassessed and no concerns were raised, so she felt more secure about her abilities. She was “very career-focussed,” she said, and “it just all overwhelmed me at the time. It was hard to see how anything was ever going to be O.K. again.”

In an interview two days later, an officer asked why one of her notes had the word “hate” in bold letters, circled. “What’s the significance of that?”

“That I hate myself for having let everybody down and for not being good enough,” she said. “I’d just been removed from the job I loved, I was told that there might be issues with my practice, I wasn’t allowed to speak to people.”

The officer asked again why she had written, “I killed them on purpose.”

“That’s how I was being made to feel,” she said. As her mental health deteriorated, her thoughts had spiralled. “If my practice hadn’t been good enough and I was linked with these deaths, then it was my fault,” she said.

“You’re being very hard on yourself there if you haven’t done anything wrong.”

“Well, I am very hard on myself,” she said.

Later, Sir David Davis and I would be told that Letby had been advised to write down how the accusations were making her feel by counsellors, something that was not used in trial for unclear reasons. That has now been reported in several outlets including the Guardian in early September [‘I am evil I did this’: Lucy Letby’s so-called confessions were written on advice of counsellors’, Guardian], including more of the notes. [NB: I cannot recall my source but I was told that Letby never puts questions marks in the notes, and this seems to check out in the original note (a reddit account BrightonBecki transcribed it here), whereas the New Yorker piece adds a ‘?’ which isn’t in the original].

Notably, the image below is actually in the original court reporting, but at least one example from a very prominent media outlet here only covers the quotations that are hostile to Letby, not the ones that could be used to defend her.

If the notes [the one in the above image being the most reported] were indeed windows to Letby’s soul, they appeared to point to two very different women and to two very different explanations.

Is it “Not good enough………I haven’t done anything wrong….Police investigation slander discrimination victimisation…….Kill myself right now…..help…..despair panic fear lost……NO HOPE… PANIC…. DESPERATE….. WHY ME…. I feel very alone and scared…… please help me”, or much more recently in her last public words at the retrial in defiance of the sentencing Judge, her standing up, turning to the court and saying “I’m innocent.” before leaving to go back to prison?

Or is it “I am an awful person…I AM EVIL I DID THIS…… HATE…… I am a horrible evil person…. I don’t deserve mum and dad…. I don’t deserve to live.”?

This alternative reality provided by the Aviv New Yorker article seemed to be showing me Letby as a human being. Letby as a daughter. Letby as a close school friend. Letby as the nurse that many had seen her as and told reporters they saw.

In this alternative reality, it seemed quite hard to see Letby the monster.

Which is the voice of sanity? Which is the voice of truth?

Are these the words of a woman who “[threw] open the gates to hell itself” [UK media], or the desperate cries of an innocent woman screaming into a void with nobody coming to help?

Are the notes a confession by the worst serial killer in modern UK history, or an innocent woman struggling to remain sane under severe pressure?

Which is the real Lucy Letby?

Lucy Letby, innocent or guilty?

I felt and feel compelled to ascertain the answers to these questions. As someone who has a nurse as a mother and a doctor as a father, the anguish felt by workers in the NHS when things go wrong, and the self blame that can occur, is familiar to me. The note did not strike me as a strong reason to suspect guilt.

Breaking through the court order: Sir David Davis’ parliamentary intervention unlocked access to a wide range of information and voices that were not yet public

Yet however hard those words were to ignore emotionally, in both directions, justice cannot be done on the basis of emotion. Indeed, emotional reasoning may be the core, root problem of this case. There were many other trial flaws cited in the Aviv piece, centering a lot on the medical and scientific evidence, but as I said at the start we are exploring that in later pieces. I highlight the ‘confession’ note here in part as I will be avoiding it in other pieces more focussed on the more critical, essential, and objectively assessable scientific and medical evidence. If the substance of the New Yorker piece held up, it appeared there was very thin evidence against Letby that appeared prima facie much more compelling than it actually was. Yet a New Yorker is no legal basis to conclude innocence, brilliant as Aviv and her team’s work was.

At that time point we, in the general collective sense of the word, obviously needed to much more robustly scrutinise and assess this quickly. But given the strong court order, doing that openly would likely be very challenging from UK territory and a potential fast track ticket to prison. I was acutely aware that I had certain advantages beyond just being able to read the article in the New Yorker. I figured it may be illegal even to raise the existence of the New Yorker article in the UK (it is now my understanding that reporting the existence of the New Yorker piece in print media was in fact certainly blocked). I did not know the law well or carefully, but I felt I had at least a little more legal safety in the US to point to the article at a high level and make clear I thought it was very concerning, and see what happened.

I decided to tweet out the New Yorker article from the US, without quoting any detail of it, knowing the link itself would be blocked in the UK. I stated that what I was reading was very disturbing, that my statement was based on that article (‘based on this’), and by implication that we needed to know more. That way I couldn’t be arrested on arriving home, but also I would be able to alert people and find others who shared concerns. Note the tweet I am quote tweeting below has 4 million views as of now - it was getting a lot of attention on international twitter. Note the ‘based on this’ caveat. It was otherwise strongly worded as I was deliberately pushing up against what I thought I could say legally to try to get people to pay attention.

Then soon after that tweet two people in my UK science and technology network reached out to me over WhatsApp and said they also had existing serious concerns about the trial. One was in a quite senior position and must remain anonymous. The other was Ruxandra Teslo, a PhD student at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, someone I knew reasonably well, and whose writing and thinking I much admire (you can follow and subscribe to Ruxandra’s X here and and her writing here in a piece of hers I particularly like on the importance of protecting weird nerds in institutions and organisations, and how people who are not weird nerds will reliably evict the weird nerds).

Together this gave me the confidence to decide I should, whilst being far from certain, escalate this issue, as I felt we needed to ascertain with much higher confidence whether what the New Yorker article was saying was accurate and how it should alter how we should think about the trial.

Now it was obvious to me that I would not be the right person to lead, probe, and scrutinise this. It needed someone much more capable, experienced and powerful than myself in these matters. At best I could play a supporting role and help out if they asked.

On reaching the required confidence about my level of concern, my mind went straight to a single MP, Sir David Davis. As he stated in a podcast interview with the Telegraph (see 5 minutes in and quoted below), I brought the article to his attention. I figured he would be the best person in the UK to work out what to do and the most likely to act if concerns were substantiated.

Why? I had known Sir David since 2020 when I was working in #10 Downing Street. As I tweeted last year following Sir David being praised in the media for intervening to protect a homeless person who was being assaulted, he had phoned me following Dominic Cummings’ departure from 10 Downing Street asking how he could help protect the Science/Tech team and our agenda in Number Ten. I found this quite impressive, and he followed through on his offer for help, advocating for us and the science agenda to the Prime Minister when our future was quite precarious.

I also knew Sir David had a long track record of defending civil liberties and of seeking to correct potential miscarriages of justice, for example in the case of Mike Lynch who tragically recently died (a case that I wish I had done more on). He was also one of the most senior and respected backbench MPs, and was a scientist by training as an undergraduate. In short, I thought David was clearly the ideal MP to look into this issue and it fell right within his area of interest and track record. It had not escaped my notice that Sir David was also the national champion of the use of parliamentary privilege.

I sent the link to him and said it appeared very concerning, then sent him the document. He called me and we spoke about it for quite some time. I don’t remember how it was left, but he had obviously already read it closely and carefully.

The next day I found he had used parliamentary privilege to raise the issue in parliament. I recommend watching the video, as I think it is a truly great parliamentary intervention.

“Yesterday the New Yorker magazine published a 13,000 word inquiry into the Lucy Letby trial, which raised enormous concerns about both the logic and competence of the statistical evidence that was a central part of that trial. That article was blocked from publication on the UK internet, I understand because of a court order. Now I’m sure that court order was well intended, but it seems to be in defiance of open justice. Will the Lord Chancellor look into this matter and report back to the house?”

This allowed reporters in the UK, some of whom I now know were already aware of concerns about the trial but unable to speak publicly about it or even report the existence of the New Yorker piece, to report on the concerns for the first time, albeit only by quoting what Sir David had said in parliament. I am now aware it also helped some of them raise it to editorial teams.

Now that concerns about the trial are entering the public discourse, it is easy to forget that Sir David’s intervention required a lot of courage as Letby was, and may yet still justifiably be, public enemy number one. He put skin in the game early and clearly.

I spoke to David again I think the next day. He was formulating a plan in stages. The first stage was to try to investigate as best as possible given the information constraints two core points, whilst making an effort not to draw hasty conclusions. These were:

Whether we were very confident it was not a fair trial.

Whether there was substantial probability Letby was innocent given the information available.

Once, and if, we were able to form an initial view on these points, we could shift our approach in favour of being more public about our concerns and advocating for a formal appeal and/or review, whilst making an effort to remain open to new information that could change conclusions. I don’t remember exactly how we phrased all this in the above sentences but this is my recollection of the spirit of it.

People began reaching out to Sir David from unexpected heights, breadths, and depths of our institutions. As he said to the Telegraph podcast August 2nd several weeks after the court order had lifted, in his opening answer:

“The reason I asked Alex Chalk [Lord High Chancellor at the time] that question [in parliament] was because I’d been rung up the day before by a previous science advisor to Number Ten, a man with a very forensic brain, and he drew my attention to the 13,000 word [New Yorker] article….. And it was quite persuasive that there were problems with the trial….. Having seen this, I thought that's slightly worrying…. And then all of these emails and telephone calls started arriving, and they weren’t from conspiracy theorists, they were from a past president of the royal statistical society, there was someone who was a very senior neonatologist, nurses, lawyers, you name it. And I thought, wow, this is not normal, this is not what you normally get with this sort of thing at all. And, there are real concerns about the evidence, and indeed the ability of the British judicial system to cope with statistical evidence, and indeed scientific evidence.”

There seemed to be substantial concern in many relevant quarters in private, and signficant discrepancy between public and private narratives. I usually take this as a sign to dig deeper. Throughout this time I was primarily a sounding board and research assistant to Sir David, as I couldn’t speak publicly due to the court order. But it was clear from those conversations that David was talking to first rate experts and was able to scrutinise and integrate those conversations, and the conclusions motivated further attention and, frankly, deep concern. Quite a number of these names are not yet public, nor is a substantial amount of the information obtained.

The court order then lifted, and on July 9th both Felicity Lawrence at the Guardian and a team at the Telegraph including Sarah Knapton simultaneously published articles raising concerns about the convictions (For international people, Telegraph and Guardian sit on opposite ends of the political spectrum).

For the first time, people could openly discuss these issues in the UK.

Pattern matching: features of the Aviv article narrative resonated with my experience on COVID response

As more information began coming to light, I began to form a mental model of how the prosecution’s case fitted together, what it depended on, and where its major fault lines may be. There were many. And the more I dug into this, the more concerns appeared to align with things I saw with my own eyes during COVID:

Group thinking: The role of group thinking in expert advice has been documented by both the Houses of Parliament select committee report and the COVID inquiry’s 1st report. People group thinking their way to ‘she is a serial killer’ did not seem a stretch to me. Nor did people group thinking their way to flawed interpretations of medical results.

Science being treated as authority, not as a social process: Science is, in my view, an open process of critique and debate, where arguments and information come from unexpected places. As Feynman said, “science is a belief in the ignorance of experts”. Yet ‘experts’ like Dewi Evans appeared to be being elevated to the role of fact providers, even despite their relatively low distinction given the complexity and gravity of the case, and were not being opposed by expert medical witnesses in the trial. Quantum computing pioneer David Deutsch’s “The Beginning of Infinity” is an excellent book to begin understanding the way in which explanations arise and how science works.

Difficulty finding the right experts: following on from the above, all experts can look the same to the non-expert, without differentiation. As someone now in the Time magazine ‘100 most influential people in AI’ list said to me last year, politicians can’t tell the difference between when they are talking to an A grade AI researcher and a D grade AI researcher. In my experience this observation generalises strongly. Likewise, the court would likely have no way of knowing that Dewi Evans was not an A tier expert familiar with the complexities of neonatology and why some babies can die in unclear ways.

Medics not thinking mathematically and statistically, and not thinking in terms of uncertainty. I saw routinely during COVID how senior medics, whilst experts in individual care, often do not have expertise in the kinds of mathematical and statistical thinking needed to probe a case like Letby’s, yet they appeared to be the sole witnesses called.

Broad poor general science literacy: even at the heights of power, literacy in basic points of science was low, and it did not seem a stretch to assume that this was also true in judicial systems and that they would not be able to see obvious flaws in the stats evidence and other evidence.

Judiciary/Legal systems struggling with science/tech: the covid inquiry is struggling to scrutinise the evidence of scientists, as Dominic Cummings and others have highlighted. I don’t want to conflate these two things too much but I may write more on this later. See my interview with Statecraft for more. Others, like the Royal Statistical Society, have recently raised concerns about how complex medical cases are handled [see their 2022 report].

In short, my own direct experience and observations made the circumstances and causal factors needed to produce the New Yorker narrative highly plausible to me. The alternative reality seemed potentially to be the real. Further, the areas of science in the Letby trial were ones that I was at least literate in (ie, I could read the relevant information and understand it, unlike, say, quantum theory), and it wasn’t particularly complicated at a technical level.

Much of what we uncovered, such as the concerns about the hospital unit in question, concerns about alternative diagnoses not considered at trial, the untested stats assumptions of the trial, and the concerns about Letby’s treatment, are now being reported in UK media. But other big stories are not yet public, though they are being pursued by reporters…. More very soon on that front.

Deep dive: an intensive look at the available evidence in August led me to conclude with effective certainty that the convictions are unsafe.

I had become quite confident already by end July that the conviction was unsafe, but there were two holes in that confidence:

I had not sat down and reviewed everything line by line, cross-referencing it, ‘all at once’ in a focussed manner, comparing the different documents that were available, as well as the wealth of private information we had obtained.

Some information was out of reach, as the full court transcripts were not available.

Point 2 remains out of reach as the transcripts are not in public domain, though we are working to get them.

Point 1, however, could be addressed, and this was what I did for much of August. The issue is that it is quite a complex case, and one of the longest in British legal history. It is quite hard to keep track of how each piece of information was obtained, what level of confidence to place on it, and, crucially, whether it was presented to the Jury, which is key to understanding whether the trial was fair and thus whether or not the convictions are safe.

Over August, I began building a set of notes structured to address this specifically. I used a range of documents but the main sources were the three judges appeal to appeal document [which declined Letby being able to appeal, available here], the New Yorker article, and the Telegraph & Guardian reporting, as well as private correspondence with leading experts (for example, conversations Sir David had had with very senior medics). Note that I place particular weight on the latter but I cannot really go into yet as some of those key voices are not yet public - Sir David has said publicly, though not identified the source, that a very senior doctor has identified alternative, non-malign, causes of death for each of the babies that does not appear to have been considered in the events leading to her conviction based on available evidence.

For example, I went through each individual claim and argument in the appeal to appeals document from the three Judges ruling, New Yorker document, etc, line by line, and identified which claims appeared to exist in public and were, or were not, considered as part of the appeals process. For this I built a paper Zettelkasten - something I will write more of later as I have found it a very useful tool over the past year.

One finding, for instance, was that the New Yorker, Telegraph, and Guardian were each reporting key facts, but they appeared to not be admitted to the appeal to appeals process (this is the process used to obtain an appeal, not an actual full appeal itself). A simple well known example is the flaws in the statistical evidence. Note that Sir David’s office has assembled all the public reporting at the time from the case, and hasn’t flagged errors in our reasoning from this, but I have not reviewed that assembled document in totality personally myself (it runs to almost a thousand pages - I will return to this challenge in a subsequent blog).

Further, basic points, such as the degree to which the cluster of cases at the hospital was actually statistically abnormal, appeared to have gone entirely untested at trial. This, to me, seemed to be a fundamental and vital point to the safety of the conviction. Further, it appeared to be a crucial building block underpinning subsequent arguments made by the prosecution. I intend to go into this in detail in subsequent pieces.

Following this I then became very confident that, unless multiple prominent media outlets were reporting factually incorrect statements in synchrony, transatlantically, on a wide range of points, yet in alignment with the publicly available court documents, then the conviction was deeply unsafe. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that the full transcripts contain unreported information that would shift this view, but it does seem very unlikely, as it would require large and complex debates in the courtroom to be missing from the public record.

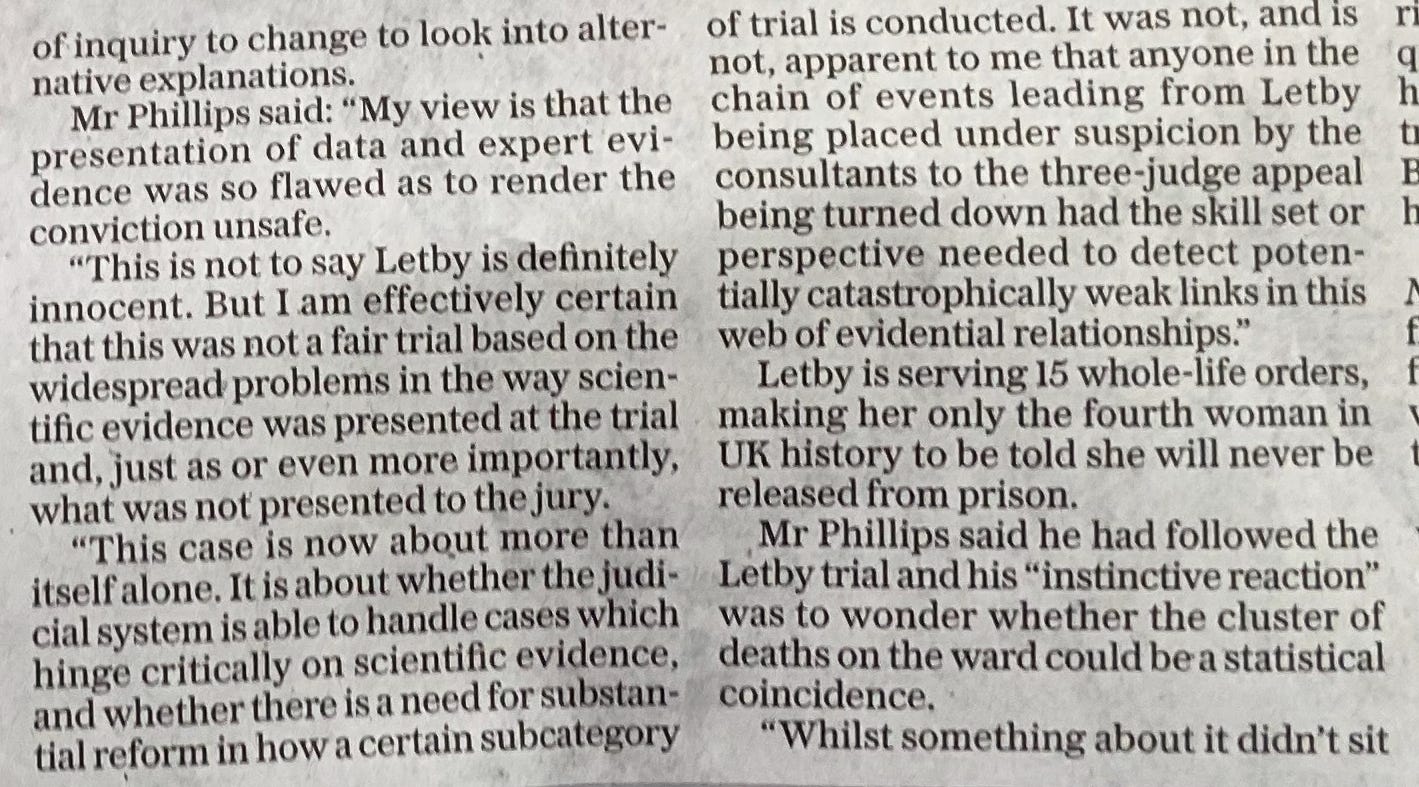

This is not to say Letby is definitely innocent. But I am effectively certain that this was not a fair trial based on the widespread problems in the way scientific evidence was presented at the trial and, just as or even more importantly, what was not presented to the jury. Furthermore, in my opinion it is not merely an unsafe conviction on narrow technical grounds, or on deep but narrow individual points of evidence, but rather on several deep grounds that seriously call into question whether the trial reached the right conclusion.

As I held in August as much of the case in my head at the same time as possible, a broad image of the trial existed in my mind as a web. The safety of the conviction depends not just on each individual point of evidence and argument, but on how each relate to each other and alter the confidence you have in each point. As a simple example, the confidence you would have in a piece of medical evidence being presented as evidence for murder via air embolism is altered by your confidence that there was an abnormal cluster in the first place. If you don’t think there is an abnormal set of deaths, you may be much less likely to interpret a scan as indicative of murder, which is a very rare thing. This is not well understood in my experience.

The more I held the case in my head in this way, the more I was able to see this web of relationships and explore it. Ie, “if no statistical cluster is clearly present, then points XYZ also collapse.” I saw ever more the same feature: a piece of scientific evidence or reasoning that looked prima facie convincing as clear and solid reason to support a murder conviction actually depended upon other pieces of scientific evidence for their solidity, and when those pieces were examined, they too suffer the same weakness, or are absent entirely. The case therefore risks being a kind of cognitive optical illusion, that makes you believe guilt with high confidence where there may be no real reason to believe so. Only when examined in close detail did the extent and severity of this become clear to me. Rory Sutherland has made a similar point in the Spectator about how statistical assumptions can fundamentally flip the perspective you take on a case (Lucy Letby and the problem with statistics - The Spectator, 31st August 2024).

It was not, and is not, apparent to me that anyone in the chain of events leading from Letby being placed under suspicion by the consultants to the 3 judge appeal being turned down had the skillset or perspective needed to detect potentially catastrophically weak links in this web of evidential relationships. It appeared to require a scientifically trained mind looking holistically at how the parts relate, and this appeared and appears still to be absent.

It was at this time that I reached the confidence needed to shift to campaigning publicly for Letby’s right to a fair trial, though I am trying as hard as I can to be open to new information that might change my views.

Open justice: Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial must be defended publicly, with open scrutiny and debate

This case involves very difficult emotions, emotions that are for most of us, including myself, in their fullest extent beyond our experience and imagination. The case and situation is truly, utterly, and deeply tragic regardless of what explanation ends up being viewed as the correct one.

I wish I had the power of voice at this time to bring comfort to the families of the babies involved, families that have been brave amidst enormous trauma. It is very important to remain aware and sensitive to those families who are, regardless of what happens next, clearly the victims of serious tragedy and trauma.

Justice, however, is rarely easy, as by its very nature it usually involves distressing things, a point others have made before me.

The deaths of those babies is a tragedy in the first instance. Then the parents of the babies have been through a trauma of the trials, where they bravely sat through the trials. And now a third trauma is emerging of questioning whether those trials were just, and whether they should have occurred at all.

Why is this third stage, in my opinion, the right thing? Why am I being vocal?

First and foremost, we must ensure the right lessons are learned so that such tragedies are reduced in the future. We owe this to all. To wrongly convict someone who may have been trying to help those babies to the best of their ability in difficult circumstances would be a tragedy, as would failing to correct the potential other reasons for the initial tragedy.

Second, there are other cases of nurses convicted of being serial killers that have substantial parallels with the Letby case, in which a supposed statistical cluster sets off a chain of events resulting in murder convictions. This case may open up ways to test the safety of those convictions.

Thirdly, if legal routes are the key to unlocking the door, then public pressure is the push that opens the door.

I don’t want to get into naming names here, but it has been suggested that out of respect for the families those of us raising concerns should do it quietly and that acting otherwise and publicly is crass and insensitive.

I respectfully (I hope) but strongly disagree with this view. I think, or at least hope, I can understand the position this critique and concern is coming from, and might, I emphasise might, potentially have had this view myself a year ago with the information I had on this trial. But now I cannot bring myself to this view.

It comes down to the literal legal foundations of our freedoms, and the rule of law and democracy: the presumption of innocence and the right to a fair trial.

A key part of this is the claim that Letby is “effectively presumed innocent” in some quarters, as a strong criticism of those who say/imply this.

But note that if the conviction is indeed unsafe, as I am effectively certain that it is, then Lucy Letby has not been found guilty beyond reasonable doubt by a jury through a fair trial, so the presumption of innocence does indeed stand. So to say that the Letby conviction is unsafe is, to my understanding, the same as concluding her presumption of innocence is intact. It's not the same as saying she is definitely innocent, nor the same as saying she should not be tried again. But it is saying that the requirements to remove the presumption of innocence justly have not been met. This is what I believe, and believe strongly.

My view is that the presentation and scrutiny of data and expert evidence at the trials was so comprehensively flawed as to render the conviction deeply and widely unsafe. Note that I take no strong view on anything presented to the court that does not fall under the remit of scientific/medical evidence. My concerns are strongly on the science/medical evidence, as I will write about shortly. I think the rest of the evidence is irrelevant if the scientific and medical evidence collapses. It is possible that a stronger prosecution case can be brought, but the existing one, in my current view, can demonstrably be collapsed, and subsequent writing by myself and others building on much earlier work will examine this. I am consciously keeping my mind open to new information that would dispel this view.

People claim that the appeals process exists, was followed, and did not uphold Letby’s appeal to appeal. But core points were not and could not legally be raised as part of that process, as is evident if you compare the appeals document with public reporting on concerns about the case. NB: Letby did not choose to use an incompetent defence appeal when it appears to me to be readily available (this is a complex issue)….

Then there is the claim that the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) route exists and it is for the courts/CCRC to deal with, not public pressure.

This ultimately brings us to the most critical issue: this case is now about more than itself alone. It is about whether the judicial system and the CCRC are able to handle cases which hinge critically on scientific evidence, and whether there is a need for substantial reform in how a certain subcategory of trial is conducted. Already, given the provably, proven, and accepted to be wrong and unsafe Malkinson conviction, there are concerns about whether these processes are sufficiently functional and timely, as raised in The Spectator recently. And this means the assumption that the courts can handle and decide this without public scrutiny may be in question here, as the Malkinson case is revealing that the judicial systems used to deal with this evidence may be flawed or prone to serious errors or delays.

Public pressure has been reliably crucial to getting injustices righted. Ultimately, public pressure will be essential to righting this potential wrong at a timescale that matters for Letby and her parents, if she is innocent.

Public pressure and scrutiny has been historically vital. The confidence we have in the judiciary as a whole depends upon not just years, but decades and centuries of scrutiny, critique, and improvement of those processes. And as the intricacy of scientific evidence brought to trial increases, our scrutiny of it must continue to make sure it is fit to deal with those challenges.

So why the Letby trial as a focus? There are many reasons. Perhaps most essentially aside from the serious doubts being raised is that it is not despite, but because of the severity of the convictions and sentences given to Lucy Letby that this trial must be highly scrutinised, as the conviction has ‘justified’ giving the state the power to destroy a woman’s life to the maximum extent short of the death penalty. If she is guilty, it is just. If she is innocent, it is an urgent matter to correct.

We must know.

The right to a fair trial is the defence against the secret police and the sudden knock at the door that dystopian novels describe. It is in our enlightened self interest to defend Letby’s right to a fair trial, as we are protecting ourselves and our families and friends by doing so. And we are protecting the nurses who care for us when we cannot care for ourselves.

Open justice and confident justice are, in the long term, not in opposition, but one and the same. That is why we must publicly scrutinise the trial, and why we must have the full transcripts.

I will write more shortly, potentially tomorrow depending on how certain things play out.

Lucy Letby’s right to a fair trial must be defended.

Please consider helping.

PS - It is quite fascinating to me how differently my US network, which has largely only read the New Yorker piece, and my UK network, which has obviously been in the UK information environment, privately reacted to my becoming vocal.

[Note I have turned off comments as I had to delete a reply that was personally abusive to Christopher Snowdon - please keep comms clean. I can be reached over Twitter. Critical and negative feedback, if polite, is especially welcome and useful. But I don’t have time to be moderating the comments right now, nor to be watching my emails to make sure I catch comments fast.].

I don’t know if Letby is guilty or innocent but there are so many questions being raised about this trial and the evidence by some of the prosecution experts that leads me to question the safety of the convictions.

One cannot deny the jury spent months listening to then assessing the evidence put to them but if that evidence is questionable it follows that the jury decisions made on that evidence will also be questionable.

One wonders why the 168 deaths at the Derby & Burton NHS Trust hasn’t pinned the blame onto a person rather than the institution.

Thank you for your insightful article. I look forward to reading about further developments. Can I suggest that in addition to obtaining the transcripts of the actual trial, you also try and get hold of transcripts of the pre-trial hearings. I would hope these transcripts would shine some light as to how evidence was considered to be admissible in court in the first place. It would be particularly interesting to have the transcript of the pre-trial hearing into the case of Baby K where at the last minute a murder charge was changed into a charge of attempted murder for reasons which are not clear.