UCL Talk - Government, science, and the need for creative destruction

ARIA, Lovelace, UK Tech position, Government reform - my talk at UCL and the Research on Research Institute

‘The ARPA/PARC history shows that a combination of vision, a modest amount of funding, with a felicitous context and process can almost magically give rise to new technologies that not only amplify civilization, but also produce tremendous wealth for the society. Isn’t it time to do this again by Reason, even with no Cold War to use as an excuse?’ Alan Kay

In May I gave the opening seminar of a new series from the Research on Research Institute, an organisation founded by Professor James Wilsdon and which is housed at University College London. The seminar series is on the need for creative destruction in what is loosely termed ‘metascience’.

I covered a range of things such as whether or not the UK is really a science superpower, reflections on ARIA & Lovelace, and the first Blair-Hague report. The ARIA section is the first time I’ve spoken publicly about ARIA, and probably the last for a long while as I’m adopting a “give it 10 years before casting judgement” attitude. The last thing they need is someone closely involved in setting it up giving a running commentary on how things are going.

In preparing the talk I was consciously pitching it toward more junior researchers/students and was delighted at how many young people came in person - we stayed for almost two hours afterwards discussing things.

Professor Wilsdon will be posting it online shortly, and I’ll update this section with it when he does. Thanks very much to him both for inviting me and for organising it. UPDATE - its here:

I’ve written it up here as reading is quicker than listening and I wanted to include some fuller quotes of the ARPA/PARC history - it's not quite a transcript, rather a typed version of the talk I gave in a slightly more essay-like format, but following the slide sequence I used.

This is a fairly rough draft, not at all polished etc, but this blog is free….

Reflections on Number Ten: government, science, and the need for creative destruction

There are three broad areas that I’ll cover, in 3 parts:

Part 1 - The need for creative destruction in how we approach science and technology policy. The status quo is broken, not delivering what it claims to deliver, and needs deep reform. Such reform will create losers, primarily the incumbent people, but be better for the UK and the world.

Part 2 - Applied metascience: the UK needs new kinds of approaches to science and technology at scale, prioritising junior researchers. This part covers some of the motivation/backstory to our team helping create ARIA, and a Lovelace ‘twin for ARIA’ we could not get through the system but that is gaining traction in the US.

Part 3 - The UK needs to rewire the state for science and technology. This covers some of the Blair-Hague reports and some personal reflections on how the UK can improve its approach to S&T.

This is only a tiny fraction of things that need to be considered in thinking about what an ambitious R&D agenda would like. Its not comprehensive. If you want a fuller view of my perspective on what an ambitious R&D agenda would look like, I suggest reading the 2 Blair-Hague reports on Science and Technology (here and here [AI]) which I was one of the authors of.

Part 1 - The need for creative destruction

I’ll start with some words I wrote with my brother in the Telegraph in 2018.

“The 2008 crisis should have led us to reshape how our economy works. But a decade on, what has really changed? The public knows that the same attitude that got us into the previous economic crisis will not bring us long-term prosperity, yet there is little vision from our leaders of what the future should look like. Our politicians are sleeping, yet have no dreams. To solve this, we must change emphasis from creating “growth” to creating the future: the former is an inevitable product of the latter.Britain used to create the future, and we must return to this role by turning to scientists and engineers. Science defined the last century by creating new industries. It will define this century too: robotics, clean energy, artificial intelligence, cures for disease and other unexpected advances lie in wait. The country that gives birth to these industries will lead the world, and yet we seem incapable of action.

…………….

In short, we should be to scientific innovation what we are to finance: a highly connected nerve centre for the global economy.

The political candidate that can leverage a pro-science platform to combine economic stimulus with the reality of economic pragmatism will transform the UK.We should lead the future by creating it.”

We referred to the financial crisis, but the article could be republished today in terms of a response to COVID without much changing. You can read the fuller article, including a comment on it by computer visionary Alan Kay who will be mentioned later, at this link.

The views that we espoused, that the UK’s economic model was broken, that the basic bureaucratic attitude of the state toward innovation was very damaging, that we needed new kinds of scientific institutions learning from historical outliers, and that the situation for junior researchers is terrible and exploitative but that this is a huge opportunity for the UK to fix, were relatively heretical at the time but the overton window has shifted a lot since then.

Some of the parts of the piece, such as improving visas, have happened (though see recent backtracking….), as has our call to create a UK ARPA (“why not replicate the defence funding agencies that led to them [the internet etc] with peacetime civilian equivalents” - the explicit DARPA ref was cut in editorial process), in part thanks to the science and technology team we had in number ten and many key allies.

But there is a huge amount still to do and these are relative baby steps so far.

Alec Stapp got 3 million twitter views simply for plotting UK productivity over the past decade.

I’m not going to cover the details of this, except to say I think fixing this is beyond the standard tool box/levers governments use. Debates about marginal differences in spending about tax levels are not going to find the solution.

It is also not about Brexit. Brexit happened over halfway through the stagnation. I don’t think anyone truly knows what effect Brexit has had, but it clearly isn’t the root cause of the problem. Brexit did not alter the line of best fit at all. Its easy to say ‘it's brexits fault’ or ‘its due to too high taxes’. Both are missing the point.

The UK was neck and neck with the United States on productivity measures in 2008. On current trajectories it will be eclipsed by Poland on some measures of wealth by the earlier 2030s. And the US is surging ahead of the EU.

I want to zero in on a specific part of the debate that I tried to push back on in government. Though it seems very niche to the current woes, It’s a point I think is especially critical.

The claim that the UK is world leading at invention but poor at commercialisation is so pervasive that it has become unquestionable. It is perhaps the founding assumption of UK R&D policy. I think this assumption is wrong.

Part of this belief came from my experiences from working in the US where it ancecdotally seemed clear the US was quite a few years ahead of the UK, at least a publication/postdoc cycle, on every area of technology intensive research I was close to (neurotech, synthetic biology, imaging technology, AI if you exclude DeepMind).

My claim, with Professor Nightingale, is instead that the UK is not a world leader in science, particularly technology intensive science of the kind that is likely to lead to valuable patents/new industries. If you’ve read my earlier blog on this, you might skip this though I add some extra commentary. The fuller paper, which was done with collaborator Professor Paul Nightingale from SPRU at Sussex, can be found here including the detail behind the plots below. It was covered in the Financial Times [World-leading? UK Science has a way to go]

I want to make five interrelated counterclaims to the argument the UK is a world leader in science:

The UK is not at the cutting edge in many key technologies even at the early stage.

UK research has become ossified and oligarchic, lacking in structural diversity, and terrible for the young.

Government has failed to learn the lessons from the most impactful 20th century laboratories, and the UK research ecosystem fails to maximise use of the diversity of types of talent that exist.

The UK system needs major structural reform at earlier stages of research.

It will need to make major changes to how the government works to do this.

This is actually good news - many of these challenges are shared issues across all major R&D systems, and it's therefore a huge opportunity for the UK to improve them with a bold reform agenda.

Existing measures used to argue we are a world leader in science are not particularly strong on closer examination:

university rankings do not solely reflect research, and are broad in subjects included

the Research Excellence Framework (REF) is a UK self assessment exercise, it is internally relevant only, and has had ‘grade inflation'

nobel prizes are a very lagging measure, given decades after.

When we look at publications data that the government uses to support a science superpower narrative (as does much of the rest of the scientific establishment), the UK is neck and neck with Italy and Canada in field weighted citation impact. Yet clearly, unless italy and canada are science superpowers, this measure is not sufficient to justify being a science superpower.

If you look only at the top 1% of most cited papers the UK position actually improves, with the UK being around 13.5% of the top 1% of work:

This is the strongest version of the world leading claim, as superficially this looks very impressive. However, we explain in our paper a wide range of reasons this is misleading.

I’ll focus here on the analysis we did, where instead of looking at the bulk output of papers, we looked at the very most impactful papers of the past decades, in the 3 key technology families identified in the Integrated Review of national strategy.

We examined the most cited 100 papers in the 3 priority tech families of the 2021 Integrated Review of national strategy (AI, Quantum, Synthetic Bio). Full methods/details here.

In this analysis, the UK rarely exceeds half of the 13.5% figure, and is often less than a quarter of that level depending upon dataset and analysis criteria. We analysed this in several different ways for each subject family, with consistent results across them. However, this is early analysis and we do not claim it is definitive. The UK is very roughly equivalent to Germany in early stage research, while often outperformed by much smaller countries like Switzerland.

Here are a couple of examples.

We looked at a recent review of the top Synthetic Biology advances of the last decade, done by UK academics. We looked at each advance and found only one of them has any significant UK link, a rate of 3.7%, or a quarter the level you would expect from the conventional analysis outlined above. The one UK one came from the unusual Cambridge Laboratory for Molecular Biology (see below).

Below shows the percentage of the very most cited AI work per year, with and without DeepMind. Without Google-funded DeepMind the UK drops from 7.84% to just 1.86%, neck and neck with hong kong, switzerland, and australia. Thanks to Zeta Alpha, an AI analytics company, who collaborated with us on this analysis.

There is much more analysis and examples in the paper, but as we say we don’t claim to be definitive and welcome rebuttals.

What to draw from this? The UK isn’t bad. But also it isn’t the extraordinary outlier it is assumed/argued to be.

Why does this matter?

Why do I care about this, and think it is so important? Why did I spend significant time after Number Ten working on this unpaid with Paul? The intent was not to trash talk about my own country.

Rather, in my opinion and experience, the view that the UK is extraordinary at early stage science is a key false assumption that derails a wide range of policy thinking and blocks reform.

Firstly, it's important to understand that summary statistics can be very misleading, and that science is driven strongly by a few rare outlier results. Michael Nielsen has made this point also. Our research systems have been optimised for producing a volume of ok work, but I fear this is at the cost of turning scientists into factory workers and depriving them of the freedom and resources to collectively pursue truly groundbreaking work. It’s not to say that a volume of ok work has no value, but it can’t be at the expense of truly groundbreaking work.

Secondly, my experience is that this point is not particularly controversial behind the scenes amongst the senior members of the UK science establishment with international experience.

Yet their public rhetoric doesn’t highlight it - quite the contrary.

As one of the most senior and powerful scientists in the UK said to me, ‘I agree. where are the nobel people’? Ie, lots of people with decent publication records, but no really game changing inventions that will bring the next round of UK Nobel Prizes. I often asked when I was inside the government what nobel-level advances the UK has made in the past 20 years using public research money. I rarely got an answer aside from Graphene (which won the Nobel) and potentially the work of Jason Chin at the Cambridge LMB.

For me it was very revealing that the figureheads of science believe one thing in private and in public say something quite different. To be clear, I am not talking about a university vice chancellor, though they are included. I am talking about some of the very most powerful people in the UK science establishment.

Thirdly, government machine is generally completely blind to this kind of thing. It really believes that we are a science superpower. This suggests a need to reform how the government interacts and understands the research system. If its advisory systems were functioning properly, they would be pointing this out - instead structures like the Prime Minister’s Council for Science and Technology reinforce the falsehood. There are published minutes to this effect.

This relates to a broader problem that government doesn’t have live contacts in the research community, ‘at the coal face’. Rather, it speaks to scientists-turned-administrators within the science establishment who, as I said above, often do not present the hard truth of what is really going on. Almost all of these people ceased to be actual practising scientists decades ago. This government blindness is understandable as its very hard for generalists to know who to listen to, whose arguments match reality, etc. And there are very few truly first rate scientists actually inside the government (people who would be on a potential path to an MIT professorship, for instance). The only way in my view to solve this is to bring in truly first rate scientists into key positions inside government. I’ll blog on this later.

This point extends far beyond this issue, for example on the crushingly low morale amongst junior academics globally. Government just does not hear the truth from the advisory groups, panels, committees etc that it uses to interface with the science community. Such groups generally, not always, advocate for the interests of the types of people who are on those groups.

If the government is to lead, be ahead of trends, and craft strong policy, it has to know and deal with reality. But all it hears is the same old reinforcements of the status quo - basically: ‘we are a world leader, give us more money, and we absolutely must be in Horizon Europe’. So far as I can tell that is the sum total of the science establishment’s vision of UK science policy. Just a polished version of the status quo - same structures, same career structure, same power dynamics. I disagree strongly with them on this.

Fourthly, it’s notable that the high impact work that drove the UK contribution to the outlier statistics that we found in our analysis was usually being done in a laboratory with marked differences to almost all of the conventional research funding structures and organisations that the UK has (LMB and DeepMind). This is a point I will explore further under ‘Lovelace’/new institutional designs, drawing lessons from these organisations.

As we pointed out, 3 US institutions including MIT have more papers in the most highly cited category than the entire United Kingdom.

Finally, the false assumption we are a science superpower is deeply damaging to policy. It blocks reform. Saying that everything is great entrenches what is in my view a profoundly broken and exploitative research system. Further, it damages the case for increased investment - saying ‘everything is great here over give please us more money’ is a complete loser in whitehall when the NHS is collapsing, taxes are sky high, and debt is through the roof. It is both dishonest AND counterproductive, at least in terms of increasing investment in UK R&D.

None of this is to say that there are not major changes and improvements needed in many other areas of the technology system, and the economy more broadly. But it doesn't help us to pretend we have a giant pile of amazing world beating inventions that we are uniquely failing to commercialise.

In closing, the Financial Times said this of the Nurse Review, setup to examine UK R&D structures, in the context of our paper:

“The question is whether the review, as well as government thinking, is sufficiently strategic or disruptive”

I think there is work to do on an ambitious plan. The UK can’t outspend other countries like the US/China, and therefore needs to look for new models of research that can outperform existing ones.

Part 2 - Bringing applied metascience to the UK - ARIA, Lovelace etc

The notion that key features of science and technology need reform, and that the current system is both highly inefficient and ineffective, is going mainstream in the United States, with articles in leading outlets like the Wall Street Journal and the Atlantic. They highlight many of the points that those of us in the Applied Metascience community have been making, and also that philanthropic capital in the US is now investing substantially in this agenda of reinventing science.

The UK has been behind the curve on this, with a few exceptions.

My own interest in this dates from observing the despondency of graduate students when I was an undergraduate, and interviewing Garry Kasparov in 2013, who called for a return to the spirit of the early postwar period in leveraging technology to drive an optimistic vision of the future. He highlighted agencies like the early ARPA as something to replicate. The photo of Garry below includes a young me on the front row (jeans, dark blue jumper)!

The Kasparov quote in that image aligns closely with what I would later hear from people like Sydney Brenner, Alan Kay, and Eric Betzig, each of whom had a nobel prize or equivalent award.

Note that ‘young’ in the Kasparov quote I think is imprecise - a better phrase is junior, which we explore in the Lovelace doc. Alan Kay, Eric Betzig, and David Deutch are all in my mind ‘junior’ despite having some of the most important technological accomplishments of the past century. Feynman is another. Rather than seek to rise through establishment ranks, accumulate power for themselves, grow a big lab empire, and collect honoraria, they instead remain at the ‘coal face’ and doing research and building things themselves, mixing with other ‘junior’ people. This is a point both Eric and Sydney made to me personally.

Around the same time, key figures in metascience like Michael Nielsen were laying the groundwork for today, for example with his book ‘reinventing discovery’.

The UK ARPA

I want to zero in now on the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the precursor to the modern DARPA. This was the main inspiration for the creation of UK ARPA, now the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA).

To understand the origins of ARPA, and what made it unique, we have to travel back in time to the early days of the cold war. When Sputnik was launched in October 1957, the United States’ sense of technological superiority was shattered. This was, as it would later be described, a major ‘strategic surprise’.

The United States had to respond quickly. There were a range of ways that they responded, but one of them is particularly interesting, what they set up did not resemble a conventional research funding bureaucracy at all.

In February 1958, barely 5 months after Sputnik launched, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) was created. It launched Project SCORE, the first communications satellite, into space in December 1958. So an early ARPA project was a success less than a year after ARPA was created.

ARPA’s mission was very simple and open ended, summarised as ‘prevent strategic surprise’ for the United States, or in its converse, ‘create strategic surprises’ for the Soviet Union. Baked into the origins of ARPA was a vision that its role was to find what others were not even looking for - it was to operate at the very edges of possibility, far from consensus, to seek out the kinds of surprises adversaries might spring on the US, and get there first. To prevent strategic surprise, ARPA was not solely and narrowly a funding agency - it was also actively seeking and crafting research areas (‘problem finding’), as I explore in the context of Licklider below.

What is most interesting, at least to me, is how ARPA was structured, and how that led to its outcomes.

ARIA was structured very differently to conventional research funding bureaucracies, even for the 1950s.

We can draw up a simple list of key features:

ARPA was an extremely flat agency. In contrast to the hierarchical bureaucracies today, there were very few layers in ARPA, consisting essentially of Program Managers, Office Directors, and then the Director, with support staff. Further, ARPA’s decision making was, and still relatively is, highly autonomous from government.

ARPA staff were much younger than is normal for funders today. The mean average age of the first 8 ARPA Directors was just 42 years of age. Or, in modern terms, roughly the age when people become quite junior professors. Some program managers even today are people in their twenties/early thirties without even a PhD.

ARPA focussed on illegible things. Today’s research funders primarily work through peer review, which means that if an idea is not clearly relatable to well known results, it is very hard to get funded. ARPA realised that those most impactful things are very often illegible to 99% of people at the time they are conceived.

ARPA had a high risk tolerance. ARPA was looking for the rare high impact outlier results, and accordingly had a high risk tolerance. If 95% of the projects failed but 5% led to great impacts, that was a huge success. Not only did it fund very risky work, it also funded and hired unusual oddballs, like Licklider (see below), who may not have made it through an open competitive application process, but had to be spotted through individual taste and judgement. People dismissed ARPA to our team by saying ‘oh it’s had a lot of failures’, which says more about them than it does about ARPA.

ARPA highly empowered individuals. Almost everyone in the agency had strong agency in their area of interest. Program Managers were able to quickly fund things based on their judgement, without layers of approval and dependence on peer review.

In very simple terms, ARPA appointed a director, who found interesting and talented people and appointed them as program managers, and then empowered them to craft and run programs with minimal interference.

Another point, which I didn’t make in my talk, is that ARPA didn’t and doesn’t today (as DARPA) really see a clear dividing line between discovery and invention in the way that other funders do.

ARPAnet and personal computing

We can look at how this works in practice.

Below is a picture of a computer in the 1950s. The computer is a whole room. You go in, provide instructions, and come back later when the computation is complete.

This was the ‘consensus’ view of what a computer could do. The default path was, loosely, more of this. Make it faster, bigger etc. I can imagine a government saying something like: ‘this is going to be important, let’s provide a state subsidy to IBM and make them build faster and bigger mainframe computers’. I’ve seen this kind of thing up close on topics today, where government funds an improved version of what we already have without qualitative change in capability. It is, in my opinion, the default behaviour of funding systems built on consensus, peer review, and very hierarchical decision structures: they reinforce the status quo position.

Yet the mainframe computer is obviously extremely different to what we have in our daily lives today.

What occurred were a series of inventions that came from a very different perspective, far from the mainstream, about what computing could do. And the research agency that supported it was ARPA.

In 1960 JCR Licklider published ‘Man-Computer Symbiosis’, which is for my money the most underrated paper of the twentieth century. Very few people I know, even those in computing/tech circles, know about its existence. Much of its language reads like it is from the future even today. You can read it here.

Licklider’s vision can be loosely summarised as “Computer’s are destined to become interactive intellectual amplifiers for everyone in the world universally networked worldwide”.

In his paper, he envisaged that humans would interact with machines moment-by-moment, such that they would become ‘symbiotic’. Computers would be accelerators and enhancers of thought itself. If this sounds crazy - it isn’t. Google Docs is an example of this. The internet is an example of this. But the vision is obviously far from being fulfilled. As Alan Kay said to me, the problem is too often the intellectual amplifier is turned down, not up, by the software we use.

It’s worth highlighting something that’s obvious but important - these kind of visions are a scarce resource. I’ve found maybe 5 people with visions even remotely comparable in scope to what Licklider envisioned, and I have been looking for 10 years. Only one of these people is even moderately well known even in tech circles. However, despite them being such scarce resources (or perhaps because they are so rare), not one of them has had their vision funded in any meaningful way, with one exception who has funding for a single isolated project.

In fact, even writing a paper like the one Licklider did is not incentivised within the system, and it takes a lot of time and effort to develop it. Michael Nielsen has an excellent post on this here. Obviously there should be a way of funding such vision development papers. Maybe I’ll do a blog outlining how it should be setup.

Now, how did Licklider’s vision end up getting funded? Below is a reflection from Ruina, who was ARPA Director in the mid 1960s when Licklider was hired as a program manager to work at ARPA.

I can’t imagine Licklider getting through an open competition process - as Ruina says, he was odd. And those kinds of odd people get filtered out by process. His vision was also so far out there that it would not be possible for him to summarise it in a few minutes for people who hadn’t closely read his work. He was not a smooth talking elevator pitch kind of guy, summarising the latest hot topic.

There was no goal or specific capability that linked them all together. Rather, it was a vision.

Alan Kay, who is a key figure in this story as we see later, summarises the role of these visions:

“‘A] great vision acts like a magnetic field from the future that aligns all the little iron particle artists to point to “North” without having to see it... The pursuit of Art always sets off plans and goals, but plans and goals don’t always give rise to Art. If “visions not goals” opens the heavens, it is important to find artistic people to conceive the projects’

What came of this? Perhaps the most striking single example is Doug Engelbart’s PhD thesis demonstration, otherwise known as ‘the mother of all demos’. I played this video in my talk and if you want to carry on reading it's best to watch it with sound:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQ8ZiT1sn88

“Flying through information space” was Engelbart’s take on the Licklider vision. Many of the inventions in that video are the first time they were ever seen.

During the creation of UK-ARPA there were a lot of people saying it should be given a ‘mission’ or a focus. The reason we fought so strongly against this is that it defeats one of the most important benefits of a true ARPA - its ability to find what conventional funding agencies can miss. Conventional funding agencies missed Licklider’s vision, autonomous vehicles, mRNA, and other ‘edge of the art’ technologies. If ARPA had been given a mission of satellite/space technology in 1958, it would have missed Licklider’s vision. It is entirely antithetical to the point of these agencies to give them a topic-defined mission, because a) it is not possible to find the right mission ahead of time, it must be discovered by the agency and b) it will prevent the agency from adapting and constantly seeking the very edge of possibility, which evolves over time. The only argument that makes sense for me to give UK-ARPA a focussed mission is that it has a small budget and won’t be able to make an impact if it spreads its bets. There is some truth to this, but that again should be a choice of UK-ARPA leadership.

How did Licklider, and his successors, operate? Alan Kay wrote to us about this when we were writing the Lovelace laboratories document [its in the footnotes]. He said:

““[Licklider] was a "nice guy" (he really was) but he also knew that enterprises like ARPA-IPTO would die if there were attempts at democracy, shared planning. etc. What he set up was "patronage" (as with the Medicis) or "MacArthur Fellowships for groups". He essentially found Principal Investigators who thought they could do something great with the vision, and Lick guessed at which ones to fund [and was willing to "take percentages" on the results]………..This worked well, and every two years there was another IPTO director -- drawn from the community -- who did the very same things.””

Or as he put it in his comments on our 2018 piece:

“It is difficult to sum up ARPA-PARC, but one interesting perspective on this kind of funding was that it was both long range and stratospherically visionary, and part of the vision was that good results included “better problems” (i.e. “problem finding” was highly valued and funded well) and good results included “good people” (i.e. long range funding should also create the next generations of researchers). In fact, virtually all of the researchers at Xerox PARC had their degrees funded by ARPA, they were “research results” who were able to get better research results”” — Alan Kay

I put the whole thing in bold text as it is all key. ARPA therefore had a strong element of community building, and was not particularly top-down in some cases (in others, like satellite technology, it operated in much more of a ‘modern DARPA’ way). ARPA was interested in growing networks of people, at least in the ARPA-IPTO office. It was immersed in the living organism of research systems, using program managers almost like ‘impresarios’ (the word Kay uses to describe them), nurturing a community united by a vision, but each with their own distinctive take on it.

At the end of the Engelbart video above, the ARPANet is mentioned for the first time that I know of publically. The ARPAnet was the precursor to the internet.

The decision to fund ARPAnet is very illustrative of how ARPA could work, how quickly it could move, and how free from modern constraints it was. Herzfeld is the DARPA director at the time, Taylor the Program Manager:

20 minutes.

The next image is of Alan Kay’s dynabook vision, again a follow on from Licklider’s vision. Guess when it was drawn?

1972. Almost four decades ahead of the IPad.

Its from Kay’s paper “A personal computer for children of all ages”: [emphasis mine]

“This note speculates about the emergence of personal, portable information manipulators and their effects when used by both children and adults. Although it should be read as science fiction, current trends in miniaturisation and price reduction almost guarantee that many of the notions discussed will actually happen in the near future…….

A combination of this "carry anywhere" device and a global information utility such as the ARPA network or two-way cable TV, will bring the libraries and schools (not to mention stores and billboards) or the world to the home. One can imagine one of the first programs an owner will write is a filter to eliminate advertising!..."

You can read more here. Kay was coming from the future, and working backwards. “Skate to where the puck is going”.

However, as I’ll explore now, ARPA stopped pursuing this style of vision-oriented research.

Some objections to this take on the ARPA history is that Licklider’s visions was a rare historical anomaly that cannot be repeated. And people say ‘well, look at the Ipad, isnt that what Alan Kay envisaged so clearly the vision carried on?’

When I speak to Alan Kay about this, he argues, persuasively to me, that the fact the IPad looks so much like what he envisaged 40 years ago shows a failure to continue invention.

He points to Bret Victor as the ‘heir’ to Licklider’s vision. This is an image Bret Victor uses to illustrate this point:

Victor’s extension of this is that there are no screens. The entire room is a computer - reality itself becomes an interactive computing device. The image below imagines a laboratory of the future where everything is an interactive computer. There are no screens. You interact by moving real physical objects, with projectors providing visual input.

This can only really be understood via videos:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=-80VsIdAHZw

I wrote a short blog on it here: https://jameswphillips.substack.com/p/s-and-t-bret-victor-realtalk-and

There is nothing in Licklider’s vision that says anything about screens. Like the ‘climbing mount improbable’ metaphor of Richard Dawkins, humanity has got stuck in a single side mountain of a screen oriented computing age on what could have been the way to a much higher peak.

Yet for a whole host of reasons, no public or commercial funder globally has touched this work. To date it has relied on some oddball philanthropists who have studied the origins of ARPA-PARC.

There are others like Victor whose work cannot be captured in conventional funding systems. He is just an example to show that it isn’t solely a lack of radical visions that is the problem.

ARPA->DARPA

Why did this happen? Why didn’t ARPA-PARC continue to fund vision-oriented research as part of its portfolio?

I want to switch to focussing on how ARPA changed into DARPA, partly as a product of the Vietnam war. It was given a much tighter defence focus, losing its open ended nature. Few people, even amongst some recent directors of US ARPA agencies I have discussed this with, realise the history of how different early ARPA was from the modern ARPAs (Kasparov was aware of this distinction and highlighted it to me, as was Dominic Cummings).

DARPA underwent a number of changes:

The imposition of a top-down mandate of focussing on defence, though DARPA still retains strong project/focus area autonomy aside from that. For example, it has repeatedly pursued areas of research that the sponsoring agency, the DoD, didn’t want it to do (for example, autonomous drones and stealth, which for various reasons were opposed by the DoD - such as Air Force DoD being full of pilots and so didn’t want to replace pilots!)

It has become more process oriented, for example the Helmeier catechisms (see below). The gentle anarchy of the ARPA has been replaced by formalism.

Relatedly, it is more focussed on a well-defined goal ahead of time (goals rather than visions). The early ARPA also had a lot of this, but it also had more open ended visions funding.

DARPA has also become what can loosely be described as more ‘corporate’. However, DARPA still keeps a relatively low key website, and its program managers are not particularly public facing. I suspect this is important to its continued success.

None of this is to say that DARPA is not still a truly outstanding global research funder, much better than the average. It was DARPA, not typical government bureaucracies like NIH, that funded Moderna over a decade ago as part of its pandemic prevention platform program (3P). But that program had a very well defined goal (I think it was something like medicines for a pandemic within 30 days of disease outbreak, with some sub specifications beneath that). Wellcome LEAP is very much in the modern DARPA mould.

Both of these approaches are needed and very important (goals and visions). Neither are really present in the UK system, at least in a program managed way. It will be interesting to see what mix of these different approaches ARIA goes for. My take is that getting visions developed is higher risk and could take more time to incubate, though I have some thoughts on how to do it. Note that the ARPA Licklider ‘vision’ funding came only 3-4 years into its existence, and it was still a minority of ARPAs overall focus.

One of the important changes in DARPA was the introduction of the Helmeier catechisms. This is often cited online as being the key to DARPA’s success, including by recent DARPA directors. This DARPA webpage summarises them:

“George H. Heilmeier, a former DARPA director (1975-1977), crafted a set of questions known as the "Heilmeier Catechism" to help Agency officials think through and evaluate proposed research programs:

What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

What is new in your approach and why do you think it will be successful?

Who cares? If you are successful, what difference will it make?

What are the risks?

How much will it cost?

How long will it take?

What are the mid-term and final “exams” to check for success?”

These catechisms have been hugely influential. And for things like the Pandemic Prevention Platform, very useful. There are problems and challenges where this mindset and approach is powerful.

However, there is a significant challenge here. As ARPA old timers have highlighted, the most impactful thing ARPA ever did - Licklider’s vision - would not make it through these filters. Licklider didn’t know what the end result of his vision looked like, could not estimate the cost, had no idea how long it would take (it is still ongoing), and couldn’t specify ‘final exams’ to check for success. So he would have failed the Catechisms test.

That these catechisms became so influential is an interesting demonstration of what kinds of things survive in human organisations: as DARPA highlighted in the text above, the Catechisms provide a very clear, legible way to explain to others why choices were made. So if asked, people can give a nice tidy interview answer. By contrast, people like Ruina, who picked Licklider as a program manager, was essentially doing it based on his judgement and taste. “[Licklider] was off doing his own thing, very imaginative guy, but off in space a bit”....He couldn’t have framed it in any known reference frame or criteria. No one was looking for or asking for personal interactive computing.

There are interesting questions around whether this kind of ‘taste’, as Ruina exhibited, can be trained, and how to identify who has it. Don Braben’s book, Scientific freedom: the elixir of civilization, addresses this and is well worth reading. Like Kay/Licklider/Sutherland, he has had only limited success in promoting this ‘taste’/impresario based approach to finding and funding very outlier and unusual people.

On this theme of how ARPA changed and moved away from the approaches that lead to the internet, Dominic Cummings found a very interesting quotation from Sutherland, who was part of the ARPA-PARC network in the 60s and 70s and made seminal contributions. He discusses how this growth of process inside ARPA then DARPA that would have restricted it from doing the internet, even as personal computing and the ARPAnet were beginning to be realised to be transformational:

Sutherland: “‘Peer review is rather more cumbersome, because it tends not to take those courageous moves. I always felt, when I was in ARPA, that one of the strengths of the U.S. government was that there were multiple funding agencies. If I was a researcher with some computer-related research idea, I had three or four places I could go. If I did not get along with ARPA, I could get along NIH or NSF, or with the Army, or the Navy, or whatever. It seemed to me that a strength of the operation was that there were alternatives.What I hope is that ARPA will not become hide-bound and tied up in a peer-review mechanism which would make it like most of the other agencies, so that it would be unable to make the courageous moves. I do not know to what extent organizational arthritis is setting in. But I sense that there is quite a lot of it. For example, the number of sole source procurement is way down.

‘The need to initiate programs and then go out with RFPs in a very rather formal way, and evaluate the RFPs in a rather formal way is stifling to individual initiative. If that is true then maybe the thing to do is to take ARPA and turn it into a stable peer-review kind of organization and start something else that is not peer reviewed, so that you have a place where individual leadership can be exercised. I do not know who in the government worries about that question. I rather suspect that no one does; that what happens happens for a variety of nonstrategic reasons, and arthritis sets in to organizations because the bureau of the budget says, "Oh, we need a new report this year and annually hereafter," and there's enough fuss from various contractors who didn't get selected that sole source procurements go out because there are abuses to that — thousand-dollar hammers — and Congress says, “Oh, we cannot have that.” On the other hand, when you cannot have that happening there’s a lot of other things that you cannot have happening too.’

There is another section of Dominic Cummings’s ARPA-PARC blog which highlights that even Licklider himself, ‘the father of it all’, became deeply frustrated at the changes in ARPA->DARPA and quit soon after:

DC: “I was recently surprised to hear someone responsible for billions of dollars of US science funding under Obama discussing ARPA clearly unaware of the basic history.The few who know something about ARPA tend to think that the modern DARPA is the same as the 1960s ARPA…….The ‘Heilmeier catechism’ that is often quoted today as the reason for DARPA’s success, including the internet, was actually introduced by the new director, Heilmeier, in 1975 and was regarded at the time as symbolic of the abandonment of the old ARPA system that produced the internet and PC. When Licklider briefly returned in the mid-1970s he was now under Heilmeier who was very different than the freewheeling Ruina and Herzfeld types. Licklider wrote a 1975 email to some of the community describing the different frames of reference between himself and Heilmeier that captures the problem with short vs long term planning:

Licklider quote: ‘In my frame ... it is a fundamental axiom that computers and communications are crucially important, that getting computers to understand natural language and to respond to speech will have profound consequences for the military, that the Arpanet and satellite packet communications and ground and air radio networks are major steps forward into a new era of command and control, that AI techniques will make it possible to interpret satellite photographs automatically, and that 1010-bit nanosecond memories, 1012-bit microsecond memories and 1015- bit millisecond memories are more desirable than gold. In George's frame ... none of those things is axiomatic — and the basic question is, who in DoD needs it and is willing to put up some money on it now? We are trying hard to decrease the dissonance between the frames, but we are not making good progress.’

DC: Licklider left ARPA a second time soon after as he disliked the new environment. By 1975 the ALTO existed and Licklider had been massively vindicated in all sorts of ways yet the system did not say — this guy did it his way and has been spectacularly vindicated, let’s listen. Instead of the wider system learning, ARPA itself changed.”

[note that until we did UK-ARPA, not a single country, even the US, had actually recreated an unconstrained ARPA agency like the original one - the UK-ARPA is the first and it took civilization 60 years to repeat it despite its incredible success].

I’ve discussed this issue at length with Alan Kay and others who were involved in the early ARPA and they concur with Licklider and Sutherland’s assessment. The word ‘freewheeling’ that Dom uses to describe early ARPA resonates strongly with my discussions about how it operated. Bureaucracy vs start-up is a framing our team used a lot. ARPA behaved like a start-up.

I’ve gone to some length exploring this as I think it is really important to understand that while defined goal oriented projects are an important element of ARPAs, they are far from the full story and arguably are not the most transformational one. In my experience, I know literally about 10 people who know at all about how all this stuff happened, despite a large amount of technological progress in past few decades coming from the worlds of ‘bits, not atoms’. There is a pervasive disinterest in the structures, incentives, and social processes through which transformative science and technology has happened in the past. Most key science establishment figures know very little about the history of science structures different to the ones they have experienced.

In short, there is more to ARPAs than modern DARPA approaches, and ARIA has the freedom to experiment with these and others they might create. The Licklider example was for us a kind of ‘litmus test’ to check if the setup of ARIA was sufficiently flexible and free to do the kind of research that can’t be well supported today.

Dominic Cummings wrote a very good blog post in 2018 on this available here if you want other parts of the story. I gave some input to that blog (I’m the ‘scientist’ referred to at the top of page 3).

ARIA’s governance

It’s not for me or the rest of the #10 sci/tech team to say what ARIA should and shouldn’t do, which positions and portfolio choices it makes. ARIA to us is like a bird we freed from a cage.

But I can talk about how and why decisions were made to set it up the way we did from inside government, and why we were fanatical in ensuring it had key freedoms.

There are a number of important features of ARIA’s governance that have not had enough attention. Unfortunately #1 is not enshrined in legislation, despite our very best efforts, but is currently by agreement inside whitehall. #2 and #3 are legislated by parliament.

Funding autonomy: It does not have to specify to government in any way which projects, areas, or even types of projects and funds it will make. This is essential, because it cannot know ahead of time what it will do. It has a mandate defined in law, by parliament, which outlines the space it is intended to operate in. Not only is there no value add in government bossing it around, it would greatly harm it if tried. This is extremely contrary to business as usual

Distant from government on appointments: only the first CEO is appointed by government. After that, only the board has the power to remove and appoint the CEO. This means that the direction of the agency is harder for government to mess with, whilst preserving oversight. The board is what the government is assessing - is the board fit to be overseeing the agency? Also, ARIA has a relatively small board of around 5 people + executives. This means those on the board are exercising real responsibility and oversight. It is not one of these potemkin boards where there are so many people on them that no one is actually exercising responsibility.

Exemption from procurement law et: there are a number of carve outs in the bill to enable ARIA to act quickly and with a minimum of bureaucracy. Procurement law can be a nightmare, for example for the LMB, in science and tech, where often what is needed is highly bespoke - if you want a very particular microscope lens, you can have to go through many months of delays, paralysing experiments and research and thus wasting tens of thousands of pounds. ARIA also is not subject to the usual civil service hiring rules, allowing it to hire people quickly.

We also studied the examples where attempts in other countries to create a DARPA-like entity had failed. This informed the decision to push so hard to get these freedoms. I’ve been asked a couple of times by other countries' governments to give advice on setting up one themselves - but it's always clear early on that they are not willing/able to give the agency the autonomy it would need to be a success. These aren’t ‘failures’ - rather, the lack of these exemptions simply turn them into clones of existing funders, with the same strengths and weaknesses.

I won’t go into the detail of it here, but the government tried to do something vaguely DARPA-like with the industrial strategy challenge fund (ISCF) around 2018. This was a multi billion pound fund run via UKRI. Despite some very good efforts by UKRI to set it up as an actual DARPA-like agency, the absence of the features (not primarily UKRI’s fault) above caused significant problems.

The National Audit Office (NAO) wrote a report on this. I never thought I’d be thanking the NAO but their analysis of these issues in their 2021 report on the ISCF was like an airdrop from heaven when we were trying to get these freedoms secured for ARIA. That report didn’t get enough attention, but within it are glimmers of the problems we were trying to solve. As an example, pg 9 of the report says that it took government 2 years to go from an idea for a specific challenge to actually making an offer to an applicant. 2 years. Most people are not interested in these kinds of details - they’d rather talk about science topics like quantum, AI etc - but to get great science/tech you have to get these details right also.

Almost all of the rest of the system is still locked in some variant of the ISCF ‘2 year delay, struggle to hire top people due to pay constraints, hiring delays due to civil service hiring rules, top down selection of areas by generalists, got to submit detailed and rigid plans ahead of time’ universe.

Another thing people don’t realise is these delays are cumulative - there are many other major delays which means things take many years which could literally take weeks with the necessary freedoms. We had precisely zero success in sorting out the rest of this system, as I’ll come back to in the final section.

I recently found an excellent thread that Martin Goodson put together back in early 2001. I found it after reading his piece on the Turing institute, but I wish I had found it when I was in government because it was exactly the kind of messaging we were trying to convey to Whitehall. Martin is worth following on twitter.

He makes some really important points in that piece that aligns precisely exactly with our thinking at the time from our own studies of ARPA and speaking to people from it.

First, there was a strong media narrative, for example in the FT, that UK-ARPA should be run by a technology investor. This misunderstands ARPA. The early leaders of ARPA were almost all specialists IN technology, not specialists in technology investing. The two things are very different, and critically ARPAs often focus on the stage of technology too early for investing commercially, and where a very different mindset is needed.

Secondly, Goodson includes a quotation about perhaps the most impactful director, Ruina (see above). ‘Ruina…… was creative, relaxed, and witty, yet serious and stimulating. He managed through discussion and suggestion, not memos; he devoted his and our attention to the top issues and the hardest problems; he got the best technical advice; he stressed the importance of leadership within and by ARPA, and he mandated his staff to act quickly.’ See above for how key features of ARIAs governance design, to remove the ‘memo management’ style and allow speed of operations, enables future ARIA directors to act in this way if they wish.

Third, Goodson emphasises the important of taste in ARPA directors - ‘Ruina knew what talented scientists and engineers looked like, because he was one himself.’ The ability to recognise ‘diamonds in the rough’ was something we looked for strongly in our search for ARIA leadership.

ARIA today

In my opinion ARIA is now in great hands.

Alongside securing the freedoms it needed, getting truly first rate people - people that would be hired into or found a world beating start up, an elite research lab like DeepMind, or be an internationally relevant University researcher pioneering things outside the mainstream - would be the foundation of ARIA’s success. As Stian Westlake has highlighted, governments find getting good appointments very difficult. I can’t go into the detail of the interview/recruitment process for privacy reasons, but all of the #10 Sci/Tech team are very confident we ended up with incredible candidates and that ARIA could not be in better hands.

Our #10 Science and Tech team spent enormous time, probably equivalent of a solid 3 months of effort, wall-to-wall in calls searching round different networks for suggestions of candidates to encourage to apply. That’s how important we thought getting exceptional people was. We asked just about everyone we could think of. We spoke to multiple former DARPA and ARPA agency Directors, Wellcome Trust people junior and senior, entrepreneurs, industry figures, UKRI leaders, academics of many varieties and seniorities, in the UK and abroad. We were looking for rare diamonds.

In Ilan and Matt we found them. I knew from my first conversations with them both that they were very unusual and extremely talented people who would stand a very strong chance of doing an amazing job.

So far so good.

What about future challenges for ARIA?

Firstly, the budget is too small and too short. In the early years the budget works well, and may even have some underspend as its very difficult to scale something like this quickly whilst keeping high quality. But at the 5-10 year horizon, the current funding levels are far too low, barely the size of a single relatively small DARPA office, whilst ARIA has a much broader potential mandate than DARPA. And the fact ARIA’s money is only guaranteed for the first 4 years creates bad incentives to produce short term results. This is manageable.

Secondly, subsequent appointments pose a risk of capture by the existing system. The board must be unusual people with unusual experiences and perspectives, the kinds of people who intuitively understand why ARIA is needed and the challenges it is trying to address. As ARIA gains in prestige, the prestige seekers who want to be on the ARIA board for prestige, rather than to nurture and protect it, will grow. It was already a substantial problem we had to fight off in other areas. That the government is making the board appointments, not the chair, makes me nervous in this respect, but this is manageable.

Thirdly, subsequent government meddling is a risk. There has been a lot of talk about political meddling. This is a risk, but I think it is much less than the risk of meddling from the Treasury. Its hard to overstate how contrary to their usual mode of operation ARIA’s setup is. This is something the network who created ARIA will be watching like absolute hawks. There are stories I’ll be able to share eventually about some of the goings on here that we had to overcome that you would literally not believe.

To get ARIA to the finish line we had to win essentially every one of those battles. We lost just one on the ‘value for money’ NAO audit rules, which we wanted to exempt ARIA from and replace with something better. The next government should legislate to stop the spectacle of a bunch of accountants trying to work out if ARIA has made good bets on science and technology. With that will come demands for more ‘process’, ‘plans’, ‘business cases’, ‘key performance indicators’, and all the things that would have made creating the ARPAnet impossible. This, along with the funding renewal point, are two major vectors for the existing ways to encroach into ARIA.

ARIA should instead be evaluated by world class technologists - former DARPA directors/program managers, Nobel laureates, policy experts with deep technical expertise, tech entrepreneurs - not by generalists with spreadsheets and a degree in politics. And that review process should be run and staffed by those deep experts, not one of these processes where you nominally have experts do it but it's actually run by other people.

The way HHMI Janelia was reviewed after 10 years is a reasonable example of how this kind of process can work, with some tweaks.

If I had to pick a small, focussed evaluation group off the type of my head it would be people like:

Arati Prabakhar (as Chair of review group) - former DARPA director, now Biden’s chief scientist

Stefanie Tompkins - Current DARPA director

Demis Hassabis - Google DeepMind CEO and co-founder

Patrick Vallance - former GSK R&D lead and former government CSA

Michael Nielsen - leading metascience researcher

Adam Marblestone - CEO of convergent research

You can vary the specific identities quite a bit, its the ‘category’ of person that matters. They could each choose a more junior person to go ‘into the weeds’ for them if time constraints are too much, having many conversations with people inside and outside the agency. People like Lada Nuzhna, Chiara Marletto, Gaurav Venkataram, Ben Reinhardt (who could also be on the main panel), Alexey Guzey etc.

Here is a list of types I would generally not have for this specific need:

Management consultants.

FTSE100 style CEOs (unless highly technical).

Financiers.

Technology investors, with some exceptions, for reasons explained above.

These categories will generally (not always) look for ‘processes’, ‘criteria’, ‘KPIs’ etc etc rather than an ‘on the ground’ feel of how the social dynamics of the agency are working, whether they are hiring creative and unusual people to be program directors, whether they are taking appropriate levels of risk across the portfolio etc. Such assessments can only be made by people who have worked in such kinds of laboratories/agencies and/or studied them deeply, though there are exceptions. The ‘KPI mindset’ can be very, very useful in some areas but it isn’t the right one for this kind of disruptive R&D endeavour, where it is the quality of the people and the creative environment they create together that is so important.

Lovelace

I then gave a compressed version of a talk I gave in 2022 to the applied metascience meet up in San Francisco about the ‘twin for ARIA’, Lovelace. I’ll post a typed version of that imminently, and update this link section once it's posted.

If you’re reading in an email browser, you’ll need to load onto the web version to see the updated link.

UPDATE - here is the link:

My Metascience 2022 talk on new scalable ‘technoscience’ laboratory designs, and potential upcoming ‘New National Purpose’ reports

I previously put out a vision document on a ‘twin for ARIA’, Lovelace laboratories [read here]. These labs were key recommendations of both of the Blair-Hague New National Purpose reports, as ‘Lovelace Disruptive Innovation Labs’. If you read that and were one of the people who asked ‘how could we make this happen?’, this blog and the follow up report m…

Part 3 - The UK needs to rewire the state for science and technology

Part 2 reminds me of a quote from Michael Nielsen - “[M]uch of our intellectual elite who think they have “the solutions” have actually cut themselves off from understanding the basis for much of the most important human progress.”

Relatedly, this recent tweet on the Manhattan project is relevant following Oppenheimer:

ARPA-PARC, Apollo, Manhattan, Bell labs, LMB etc etc all point to very different ways of organising R&D than the near-universal 'request for proposal' (RFP) approach. We have forgotten the roots and methods of much progress. Something that isn’t appreciated is that much of the methods and approaches used in these programs would be outright illegal in the UK context today, and if not illegal essentially impossible to get through the Treasury-DSIT -UKRI bureaucratic loop.

I had hoped COVID could have a silver lining of being a learning lesson, but if anything the wrong lessons have been learnt. Reversion to norm was rapid and decisive. Almost all of the key people who made crucial differences, many of them junior civil servants, have not only been forgotten but have left Westminster.

I’ll start with a few observations on why R&D is so challenging for governments to get right.

Its challenging for generalists to understand how R&D is practised in reality. The human element of science is vital. Its more akin to an artist’s studio than a factory. The polished grant applications and research papers that come out of science bear little relation to the messy, ‘foraging in the dark’ way in which much of science is actually done. Further, unlike policy areas like health, crime etc, most people have very little exposure to how scientific systems work in their day-to-day experience.

Research is extremely variable as an endeavour - there are few if any policies, rules, or conclusions that truly hold across all endeavours of science. This is very different to many other areas of policy, such as education, where there are key common elements to all primary schools, for instance. In science, even something as fundamental as publishing one’s results varies substantially between fields like medical research and AI/physics.

Research is also highly internationally interdependent, both collaboratively and competitively. This is a topic for another blog.

Research is unpredictable and exploratory by intent, but government processes are designed for the exact opposite of that. Most government processes, including in the Treasury, are built and oriented around a plannable, knowable future. Yet while research is very different to building hospitals and schools, very similar government processes are often forced onto it.

Research is based on disrupting the center. The processes of research continually disrupt, overturn, and extend what we know. So it is always changing. The key people are also always changing. Expertise in the past may not be expertise relevant to the future. Perhaps most importantly, the notion of a ‘scientific establishment’ is something of an oxymoron, since science should have no authority. As Feynman said, ‘science is a belief in the ignorance of experts’. I’ll do doing a blog on this issue soon. Yet most government processes operate by finding very senior people ‘known to the government’, with honours, seats on illustrious committees etc. An example of where this can go wrong is in the AI council/Turing institute.

Blair-Hague report - 3 areas of improvement for government

I can’t summarise the entire blair-hague reports here. But I’ll pick out three things that I think are important.

The first is the need to enact fundamental reform of how the British state invests in R&D. There is a lot of focus on how much the UK invests, but very little on the processes inside government, particularly the Treasury, used to make those decisions. How money is spent is just as important as how much, perhaps more so.

HM Treasury - the most important target for reform

We go into this at some length in the report.

There need to be much longer term spending settlements. UKRI, until 2021, existed on single year spending settlements. This paralyses institutional planning, locks things into short term targets, and creates risk aversion.

The audit culture relating to R&D funding needs to be essentially entirely binned in many places, not just trimmed back, and replaced with expert review. The Cambridge Laboratory for Molecular Biology (LMB) in its heyday put in one five page report every 5 years, summarising what it had discovered. Today this exercise has grown to 4 500 page reports, a 400-fold increase. It's the difference between the blurb of a novel vs an entire lengthy novel. In my opinion this is absolutely farcical. Further, in my experience nothing is ever done with encyclopaedias like this, at least at the level where significant decisions are made. And it's like this across the board - if it is that bad at the LMB, a crown jewel of UK research with at least some ability to push back on it, imagine how bad it is in places without the LMB’s record. Until you have seen this with your own eyes it's hard to understand how badly bureaucratised everything has become, and how much endless paperwork trails have replaced expert judgement and analysis.

Instead of this system, I would have expert reviews of the kind outlined for ARIA above, at least for our most significant R&D labs. This is a broader point that expert review, preferably international, should replace generalist audit.

The government also needs to think differently about how it invests in R&D at a ‘macro’ level. If I could put one plot in front of the Prime Minister, it would be this, showing that private R&D investment is crowded in by public R&D investment:

Ie, there is a strong correlation between public and private R&D spend levels globally amongst advanced economies. There is at least some recognition of this inside the Treasury.

However, the way it is done, in a kind of ‘spreadsheet way’, is very poor and counterproductive.

What happens is they say: “we will put up £1 of public money if industry puts in £2, on a line by line basis in the spreadsheet”. Yet the benefits of public R&D spend do not clearly and legibly manifest in immediate private R&D investment in most cases, and so can’t be considered by a kind of command and control system where the Treasury wants every minute investment to be backed by private £, and to know what that partner is. An example is the funding for Demis Hassabis’ PhD in neuroscience, which led him to found DeepMind. That small investment of a few £100k maximum translated into around £10billion of inward investment from Google into DeepMind over the last decade, but there is no way a spreadsheet inside Treasury could capture or predict that.

This is particularly damaging as this system reinforces incumbent players who can commit large amounts of investment up front, and it is also very challenging/impossible to know if they would have gone ahead with the full investment even if the government had not partnered with it. The entire Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund was done in this way, as were key decisions when I was in government.

Think back to the giant mainframe computer vs Licklider example: this ‘industry partnership’ mindset risks leading you to subsidising IBM to build a bigger mainframe, not fund the project that led to personal computing and the internet. That isn’t to say industry partnership is bad at all, but rather the mindset the government uses has very significant drawbacks.

My own view is that reforming this can’t meaningfully be done without breaking up the Treasury. I’ll go into that later elsewhere. Since 1990, a series of changes including Gordon Brown centralising power to himself in the Treasury as a ‘shadow number ten’ and the Cameron/Osborne austerity era greatly increased the granularity with which the Treasury controls spending.Treasury is currently the de facto controller of national R&D strategy due to the extreme control it exercises over spend, which didn’t used to be the case. And these processes and approaches are so deeply ingrained into how the modern Treasury works that they guard them like a dragon guarding its gold hoard, despite them making little to no sense in the context of R&D spend.

The second key area to reform is upgrading Science and Technology expertise at the centre of government.

In the Blair-Hague reports we called for a central science and technology unit, in number with people joint with the new department.

In a nutshell, something cannot be a priority of government without it also being a priority for the center of government. Something being a priority means, literally, it is a priority over other parts of the government's agenda. When key decisions are made, you need people close to the Prime Minister who can influence in the direction of R&D. And having people in the center elevates their power within the system.

One of the reasons this is so important is that many of the basic issues facing R&D in the UK come from deeply ingrained features of how the government operates, which can only be changed by the center of government. Audit culture, low investment levels, Treasury’s command-and-control mindset, NAO ‘Value for Money’ investigations, procurement/hiring rules which cause long delays, the need for new approaches at scale - none of these can be done without a Number Ten that has the skills, understanding, and motivation needed to drive major reform.

I was asked both before and after my talk why we focussed so much on ARIA rather than fixing the rest of the system. The answer is we did try, but it proved impossible after Cummings left to fix the deeper rooted problems. Only if it was a high priority of government could this be fixed.

Part of the motivation for this unit involves bringing in deeply technical people alongside the generalists. You need people who can exercise judgement and ability to assess credibility, otherwise you become captured by the most senior stakeholders/voices. It’s difficult to do this unless people have real experience in world class research environments and ecosystems. Such people can help find and bring in voices outside of the usual suspects, and go beyond credentialism as a way of selecting people to give input to government.

There are also obvious dangers with R&D becoming a priority of the government, and I saw some of them: the government can bring its problems and impose them onto the R&D system, increasing the issues I spoke about before. For example, as R&D goes up the priority and prestige list, so too can the pressure to appoint people for non-merit based reasons (such as donors or friends).

The third area is to ‘give power to the young’ throughout the R&D system.

“I strongly believe that the only way to encourage innovation is to give it to the young. The young have a great advantage in that they are ignorant. Because I think ignorance in science is very important. If you’re like me and you know too much you can’t try new things. I always work in fields of which I’m totally ignorant……Today [we] have developed a new culture in science based on the slavery of graduate students…….The most important thing today is for young people to take responsibility, to actually know how to formulate an idea and how to work on it. Not to buy into the so-called apprenticeship.”

Sydney Brenner, a pioneer of molecular biology

This quotation from Brenner captures a basic issue in the way we now think about science and technology. I’ve got a mostly written lengthy blog on this issue, so I’ll just provide summary detail here.

Brenner’s vision is of science as a disruptive, creative processes, based on new ideas from people outside of the establishment. In this model, you should always be on the look out for talented junior people outside of the existing structures.

This is in contrast to what we might call the ‘authority’ view of science, in which as people accumulate more knowledge, they become better scientists. In this model, you want to empower people who are as senior possible. This model assumes that knowledge, in a clearly explicable, logical way, leads to new breakthroughs.

In fields with very clear, stable knowledge, like classical mechanics, seniority can be very useful, especially for teaching.

But in fields that are changing beyond recognition, or in fields which haven’t actually made meaningful progress (like much of AI pre-deep learning, and arguably much of circuits neuroscience around 2010), that knowledge can becomes a curse, and leaves you trapped with the wrong ‘expertise’. This from Eric Hoffer, American moral and social philosopher, captures this well.

“In times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists”

I’m not saying one perspective is better than the other. Rather, that the balance is very awry in the UK system and the academic system more broadly, which prioritises credentialism and seniority over creative promise. I often saw processes to appoint people into government positions, and they were simply long lists of committee memberships and honoraria, with no consideration whatsoever of what the person had actually done, why they were distinctive, etc.

This has an additional trap in that only a subset of researchers play this credential building game, and in my own narrow experience most of the genuinely creative scientists don’t play it.

I started this part of my talk with a quote from a senior official which I think is spot on:

“The big problem is the machine thinks we have to engage with the most important people, and they equate that to the most senior people. But in science, the most important people are those with a decade of genius work AHEAD of them, not the senior people” Senior Whitehall Official

This matters for a whole host of reasons I’ll explore in a separate blog. But it’s useful to pause and consider why UK R&D looks much the way it did 70 years ago, but with greater concentration of power in senior hands and less diversity of approach. The reason for that is partly because the system works well for those who end up sitting in front of ministers, and they advocate for a continuation of that system.

You have a self-reinforcing club at the apex of power in the UK science establishment which ultimately ends up defending itself and advocating for its own interests, even if the individual players are well intentioned. The mismatch in the outcry over Horizon Europe, versus the situation faced by junior researchers, is but one symptom of this. Ultimately, the system largely works well for them, so there is no pressure for meaningful and bold reform. Part 1 of my 2019 notes here covers some of the major structural problems in R&D relating to risk aversion, exploitation of junior scientists, and the collapse of research culture.

As I recently tweeted, the average age of admission for a new fellow joining the Royal Society is 61 years old. Just 14% of fellows are under 60. This is far beyond the age at which Einstein, Curie, Lovelace, Watson, Crick, Brenner, Newton etc made their great discoveries and inventions. This means that in practice the royal society is a collection of former scientists turned administrators/retirees, rather than people at the coal face. And there is a big difference between hopping between cocktail parties, committees, and grant applications, versus actually spending the large bulk of your time reading and researching at the cutting edge. A lot of these senior experts are very out of touch with the actual global cutting edge beyond the Oxbridge Senior Common Room chatter. I could give many examples…..

There are many people inside these organisations, at senior levels, who agree with this assessment in private, and are supportive of a reform agenda.

We can see this problem globally, and the scale of opportunity, showing how the amount of funding in the US NIH has shifted dramatically from young people to senior people in the past few decades:

This means there is an enormous pool of exceptional junior talent looking for opportunities…..

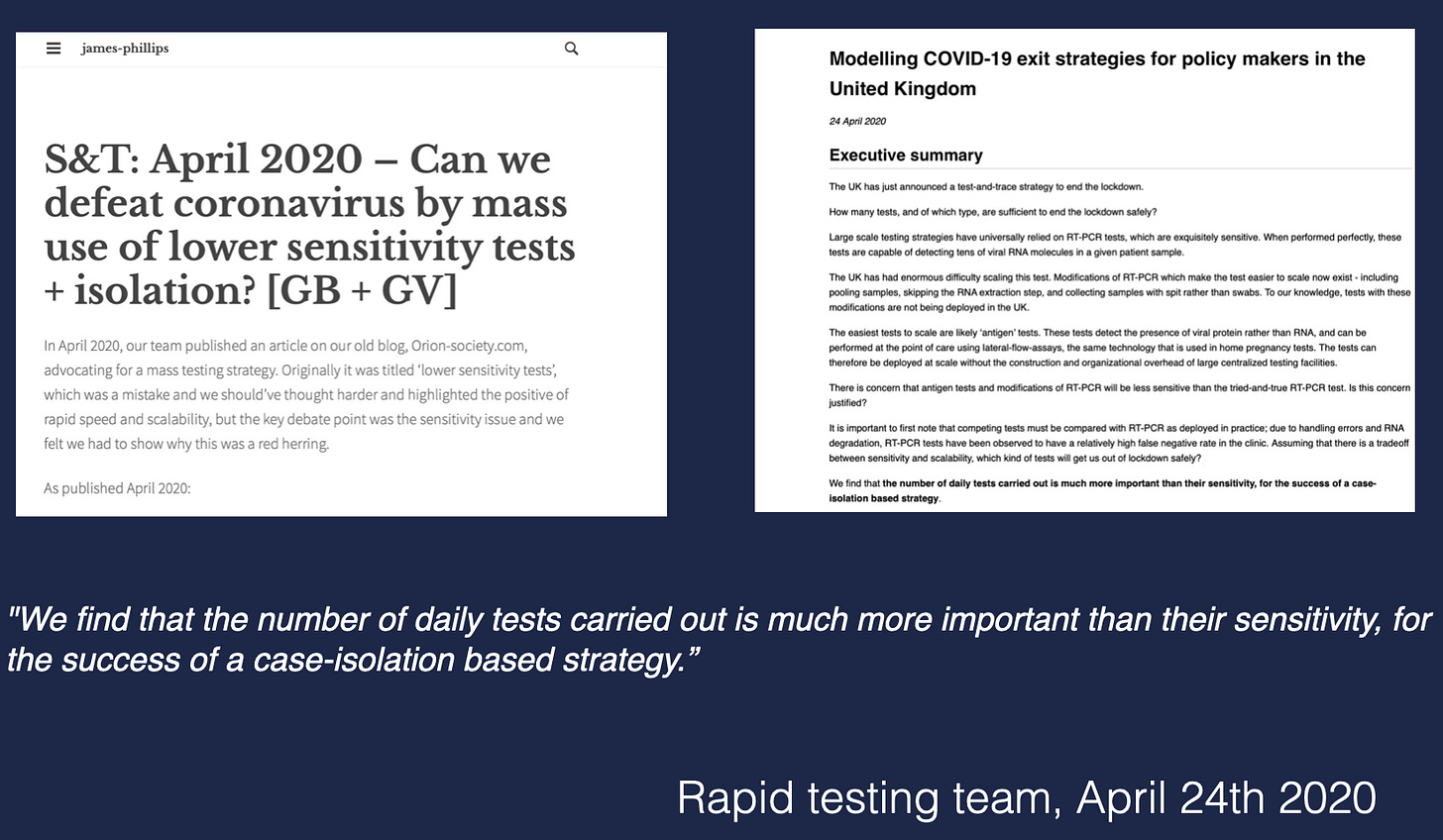

I’ll close by saying that during COVID, the most critical people in getting the UK into pole position on using rapid testing were almost entirely junior. It did not come from the senior advisory groups, and in fact was blocked by several of them for some time as it didn’t look like they expected and they literally could not understand the basic argument, as it overturned key orthodoxy on how a pandemic should be contained.

In April 2020, many months ahead of it becoming close to government policy, our junior team modelled and found ‘that the number of daily tests carried out is much more important than their sensitivity, for the success of a case-isolation based strategy’.

Slovakia, inspired by our program, actually did what we suggested and were trying to do, and found it was equivalent to a full lockdown in suppressing the virus (see below published in Science).

Again, none of those who were mission critical in the early stages got the slightest recognition for it. I’ll tell the story of this later. Hopefully the inquiry looks into it. It’s a very telling example of how great ideas don’t come from the existing senior committees, and the government needs to be on the lookout for whats happening at the edges.

On grad students: definitely feel there is growing recognition of this amongst my faculty colleagues in the US, and amongst UK faculty who I’ve spoken with.